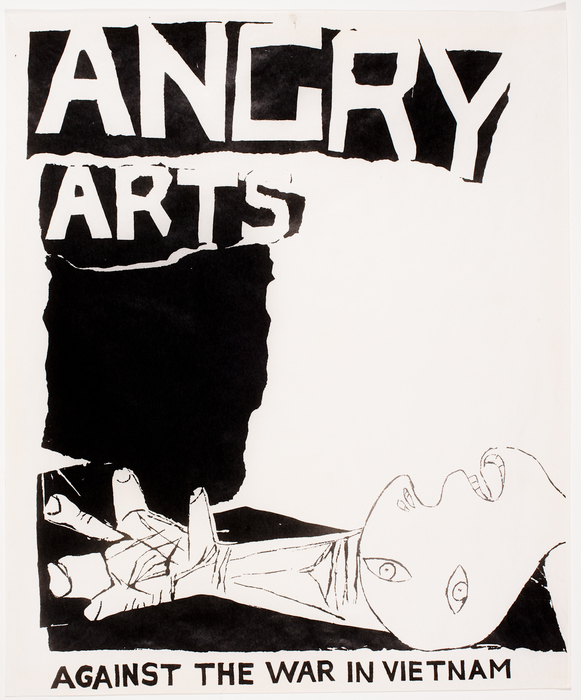

Angry Arts Week

Collage of Indignation

“We, the Artists and Writers Protest, call upon you to participate in a Collage of Indignation, to be mounted in the cause of peace, from January 29 to February 4, 1967, at Loeb Student Center, New York University. Titled The Angry Arts, it will feature, in a context of happenings, poetry readings, films, music and theater, panoramic size canvases, upon which you the artists of New York, are asked to paint, draw, or attach whatever images or objects that will express or stand for your anger against the war . . . We are also interested in whatever manner of visual invective, political caricature, or related savage materials you would care to contribute. Join in the spirit of cooperation with other artistic communities of the city in a desperate plea for sanity.” M.Israel, Kill for Peace: American Artists Against the Vietnam War, University of Texas Press, Austin 2013, p.70.↩︎

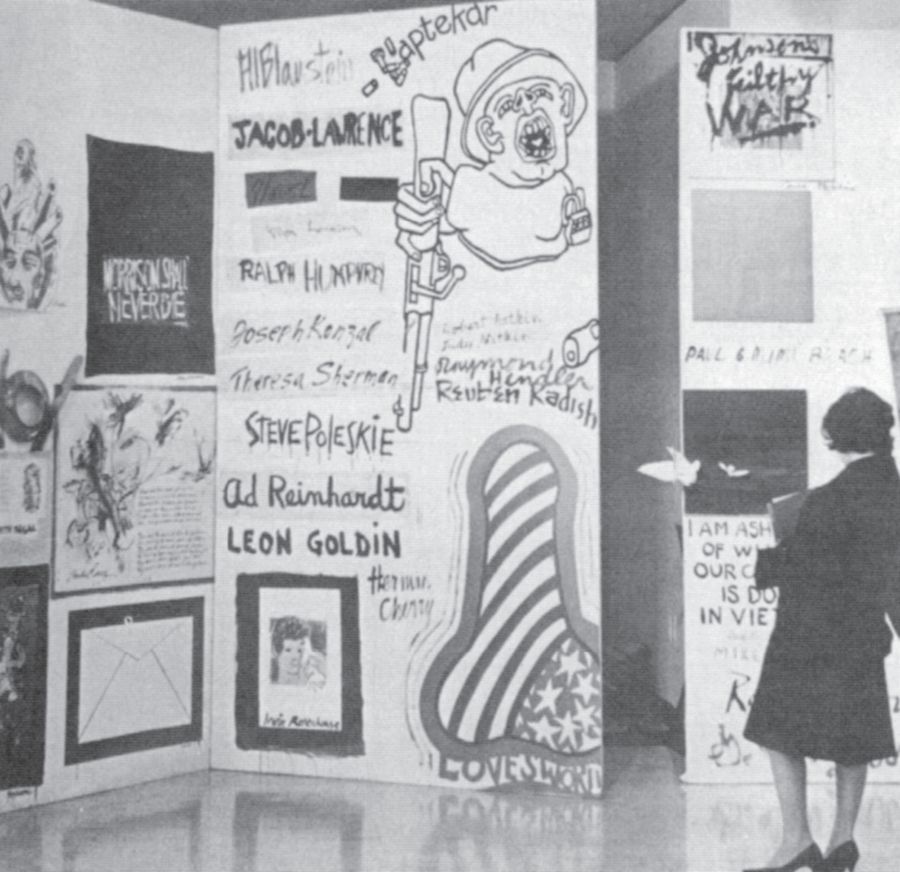

The response to the call disseminated under the AWP logo was massive. More than 500 artists took part in the Angry Arts Week which encompassed concerts, shows, performances, exhibitions and public addresses. The keynote event was the Collage of Indignation, a huge (3m x 36m) object and exhibition consisting of several walls covered with canvas, densely packed with anti-war paintings, drawings, objects and interventions made by hundreds of American artists:

“Though its various contributors represented a number of artistic schools of the period, the Collage’s components were most often angry tirades of words stylistically derived from graffiti, political posters, and cartoons, akin to those works made by the Peace Tower’s “artist–citizens.” Examples of note were Jack Sonnenberg writing into one of his abstractions; Mark di Suvero burning words into a rusty piece of metal; Petlin’s “unflattering image of LBJ” captioned with “Johnson is a murderer—In Memory of Women and Children Killed by Bombs in Vietnam”; May Stevens’s scrawled “Morrison Shall Never Die” (referring to Norman Morrison, who immolated himself in 1965 to protest the war); and Nancy Graves and the activist group Black Mask writing “HUMP WAR” and “REVOLUTION,” respectively. 22 Other artists, like Jacob Lawrence, just wrote their names. Fraser Dougherty submitted his draft card.” Ibidem, p.74-76.↩︎

“While at NYU, the Collage attracted roughly ten thousand people. Many of the organizers, saw the Collage as a landmark effort, the noble public rebirth of political activism in New York, dormant since the 1930s, and a visual success. Regardless, the Collage did not impress the media. As with the People’s Flag Show three years later, it was criticized principally for its prioritization of instinctive, angry scrawl and for its low level of creativity. In the New Yorker, Harold Rosenberg said the Collage looked as if it had been made according to “craft standards.” Ibidem.↩︎

Film, Theater and the Caravan

In addition to the Collage being the main attraction, the program of the Angry Arts Week included also many other events drawing on various form of artistic protest. The whole week was filled with exhibitions, shows, meetings, manifestations, performances and happenings. Examples of notable contributions to Angry Arts Week were Werner Bischoff’s installation of photographs titled Life in Vietnam; a “war toy” exhibit; a conductor-less concert at Town Hall “to symbolize the individual’s responsibility for the brutality in Vietnam” and a “Contemplation Room,” which featured more than two hundred color slides of everyday life in Vietnam combined with WBAI radio reports on the war crimes.

During one of the film and theater nights, a show of Carolee Schneeman’s pioneering film Viet-Flakes. The film shot on the turn of 1965 and 1966, consists of a series of static images showing the brutality and horror of war, in particular dead and mutilated bodies. Schneeman collected such documentary photos cutting them out from newspapers and magazines for a number of years.

To create the work, Schneemann laid out the collection of photographs she had compiled over five years in arcs on the floor and obsessively and quickly zoomed in and out on individual examples (often over and over) with her camera, so that the eye never rested on any one image or even brought a singular image into focus. Coupled with popular songs which were abruptly cut off and restarted the experience of viewing Schneemann’s flashing onslaught of collected photographs is disorienting and nauseating.

During the Angry Arts Week, Peter Schumann’s legendary, left-wing Bread and Puppet Theater founded in 1961 also performed. Their performance featured a physician lecturing to medical students about the consequences of using napalm and the treatment of different kinds of burns. Gradually the performance launched into a torrent of information about the Vietnam war. For a number of hours the audience was flooded with facts and figures of casualties and deaths, rapes, instances of violating the international war laws, costs of the conflict and the resulting political situation. All that was presented against the backdrop of documentary photos and recordings showing the consequences of the war, destroyed cities, victims of bomb raids and people burned by napalm.

Additionally, the Angry Arts Week had its mobile platform – a flatbed truck converted into a multi-purpose stage hosting a continuous stream of performances, speeches, lectures, concerts and photo and video shows. The truck was decorated with anti-war artworks, flags and posters and the artists, singers, actors, intellectuals and activists traveling on the truck distributed to the passers-by leaflets designed by Rudolf Baranik with information about the Angry Arts Week and the choice of anti-war poetry.