Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp

“The base wasn’t marked on the map, so I walked up to where I thought it might be, and hit upon this area with five fences and military vehicles going between them. The common itself was quite beautiful: birch trees, silver trees, butterflies; but the ugliness of the military might was quite shocking. It was where they were building the silos for the cruise missiles” https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/mar/20/greenham-common-nuclear-silos-women-protest-peace-camp [accessed on 29.12.2018].↩︎.

Protect and Survive

In 1980, the nuclear war threat was very real. The UK government distributed brochures and posters with information and produced short training videos and audio recordings broadcast on the radio and TV with detailed guidelines what to do in the event of a nuclear blast. The government’s information campaign entitled Protect and Survive described the alarm system which would be activated in the event of a nuclear attack. In June 1980, as part of the defence measures, the French Minister of Defense Francis Pym decided to locate 160 nuclear warheads in the Greenham Common military base in Berkshire. The cost of the operation totalled GBP 16 million.

In response to those actions, in August 1981 thirty six women who called themselves Women for Life on Earth, six men and their children marched off from Cardiff heading for the Greenham air-force station in w Berkshire (covering a distance of around 120 miles or 193 km) in order to protest against the placement and storage of American cruise missiles on the territory of the United Kingdom. The Group required a meeting with the UK government and holding an open debate about military activities in the united Kingdom. But their postulates were rejected. In order to attract the attention of the officials and the media, the women decided to set up a peace camp and began to occupy the main entrance gates to Greenham military base, chaining themselves to the base fence.

“[At camp] in the evening when it was dark it was much quieter and we could sit round the fire, talking and cooking. Mainly we were there to see that the cruise convoy did not leave the base by any exit”. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-berkshire-41199648 [accessed on 29.12.2018].↩︎.

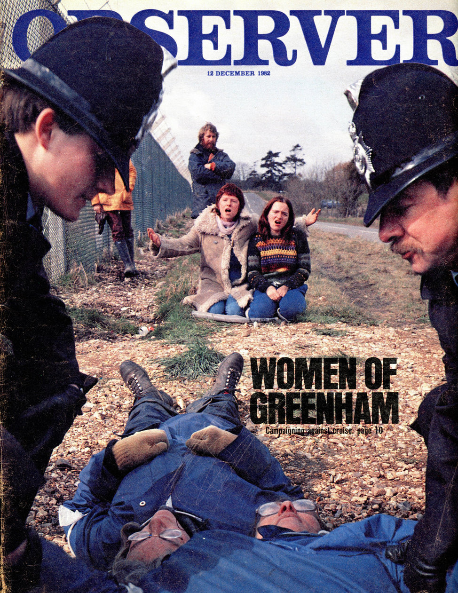

“Before the first blockade we were all really frightened. None of us had done anything like this before; would the police be rough? Back at the beginning there were men involved, although it was a women-led initiative. But one day a bulldozer arrived and wanted to drive through the camp. We all spontaneously sat down”. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/mar/20/greenham-common-nuclear-silos-women-protest-peace-camp [accessed on 29.12.2018].↩︎.

“At the first blockade, we walked out to fill the main gate at 6.30 p.m., with policemen and lights in our eyes, and we sat down. Women were doing the same at six other gates. The rain poured down steadily and we sat there, wrapped up, throughout the night, taking turns to do four-hour shifts. People brought us hot tea and played fiddles – there was a good, friendly atmosphere. It was a very gentle action. No one was waving or screaming or holding confrontational banners, it was just women using their bodies to block gates, which was highly symbolic. The police were a bit bemused. In the morning, we discovered the base intended to work as usual – they had created a new gate. A policeman told us this was their gate, and if we sat there, we would be arrested. He was very courteous and gave us five minutes to think. The decision was unanimous, and the first group of women sat down”. Ibidem.↩︎.

Embrace the Base

Throughout the next year thousands of women arrived at the camp which gradually spread along the entire base fence over the length of 15 kilometres.

“I always thought that if I was an artist or a poet I would have a voice, but the only thing I could do was sit in the mud. A friend told me about a march from Cardiff to Greenham to highlight the missiles, and afterwards a few people had stayed on. When I arrived there were just a couple of tents and a campfire, but it was a relief to be finally doing something”. Ibidem.↩︎.

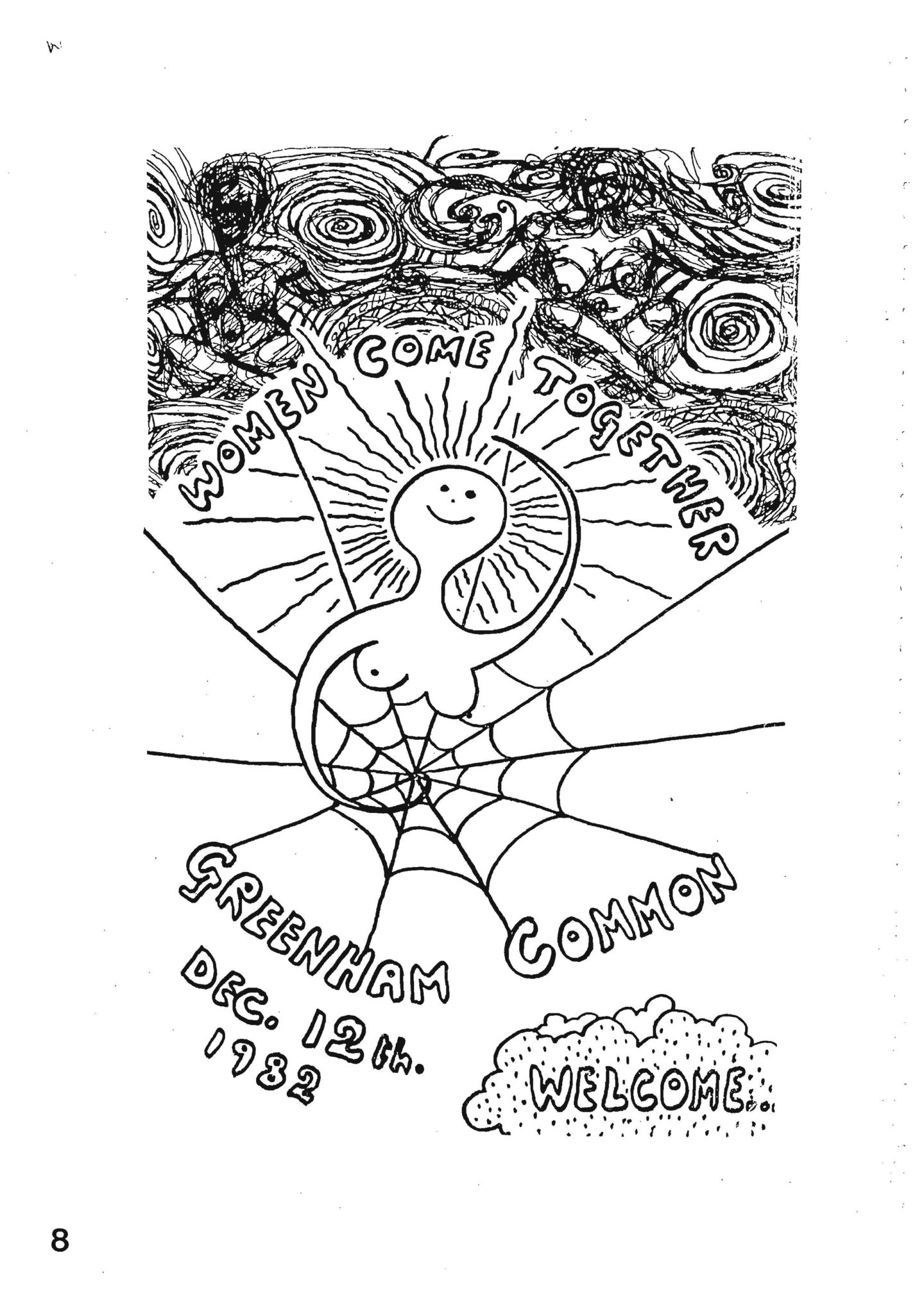

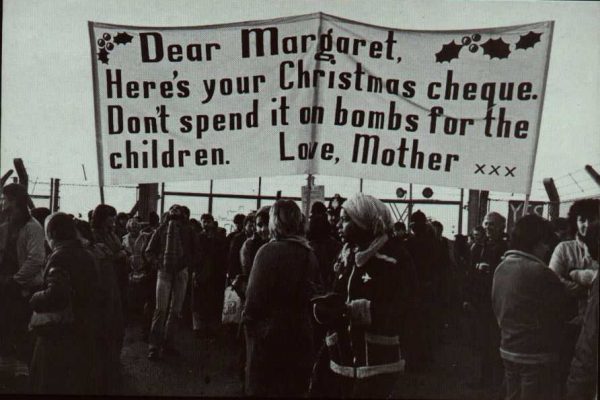

In 1982, a letter was sent from the Women’s Peace Camp with an invitation to join the Embrace the Base campaign. In effect, 30,000 women surrounded the base holding hands. Such a huge gathering had to finally attract the attention of the media.

“Embrace the Base was different; it was unique. This was when 30,000 women slogged down the motorways. I went down from Leeds on the M1. As we passed the service station at 5 a.m. we could see other transit vans full of women and giggled at each other. There were traffic jams to the base, it was very exciting”. Ibidem.↩︎.

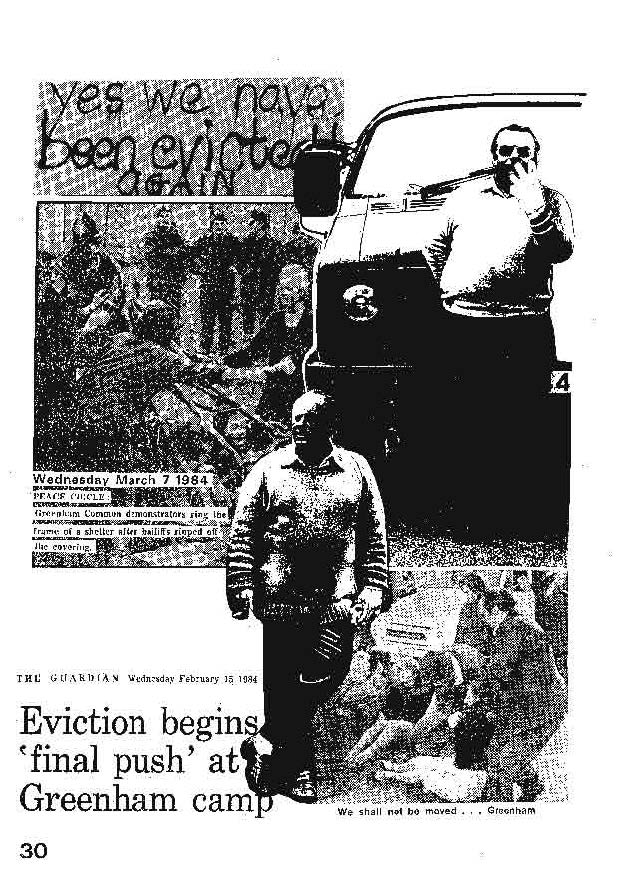

“We had the Embrace the Base demonstration that December. Afterwards there was a great build-up of helicopters overhead, with lights day and night. They had police outside the nine-mile perimeter fence, and they had British army personnel just inside the fence all the way round, so you were never alone. At one point police would follow you into the bushes, it was quite unpleasant. We were constantly being attacked with things like maggots and pig shit, and the tents would get slashed with knives, so it was scary. They would evict us constantly, which meant you had to be able to leap up out of bed, fold up your tent and get it into a van. Because of the bylaws, they could seize your property but not you, so when the bailiffs came each gate had a van that drove you away and brought you back when they had gone. If they saw any signs of weakness in us they would come several times a day”. Ibidem.↩︎.

Women’s Camp

In 1982, the participants decided that the Greenham Common camp would be open only to women. Their decision was motivated by a conclusion that the protest would be more effective if they relied on their identities of mothers and caretakers who may lose children in a nuclear war. The main argument to convey to the public was their concern about the future generations. The idea for peace protests was quickly picked up by other groups of activists and similar camps were set up around several other military camps in the United Kingdom.

“As a young woman it didn’t feel like a question of if the bomb dropped, but when. Even people who weren’t against us having nuclear weapons were terrified of nuclear war. I was divorced and my children, who were five and 12 at the time, were living with their father. I felt like when the bomb dropped I wouldn’t be able to even hold their hands, so I just wanted to do everything in my power to stop it”. Ibidem.↩︎.

“In February 1982 the decision was made to make the camp women-only. That was really significant for the blockade in March because it was the first women-only action. I remember the energy and desire and creativity and courage of women who were doing civil disobedience together; it was extraordinary. I was watching and photographing women who were laying bodies on the ground, who were blocking entrances right around the nine-mile perimeter fence”. Ibidem.↩︎.

Women taking part in the protests against the government’s actions were presented in the media as criminals, hippies or even witches. Counterarguments were put forward: if they cared for their children so much why wouldn’t they stay at home with them? The activity of the Women’s Peace Camp was treated as a threat to the traditional family and conservative values.

“It was a shame but it made it more empowering for women. People think everyone at Greenham Common was a hippy, but many were ordinary women who did the cooking, and whose husbands played golf and didn’t mind them coming because there were no men”. Ibidem.↩︎.

“In the early days the public was very supportive. I would dress smartly and go to Newbury with a clipboard, asking people to come and have a cup of tea with us at the camp. Many did. After the fence went up around the base I went to a department store in my tweeds to speak to the manager and said, “What I would really like is some chains, padlocks and bolt cutters.” And they gave them to me!”. Ibidem.↩︎.

Tweed suits were certainly not the best choice for daily life in the Greenham Common camp. Women lives in tents regardless of the season of the year and weather conditions. Heavy rains were most difficult to put up with. They did not have access to electricity, telephones or running water and were constantly exposed to a threat of eviction or attacks. Despite that, women from all parts of the United Kingdom and abroad arrived at the camp to resist nuclear weapons.

Forms of Protest

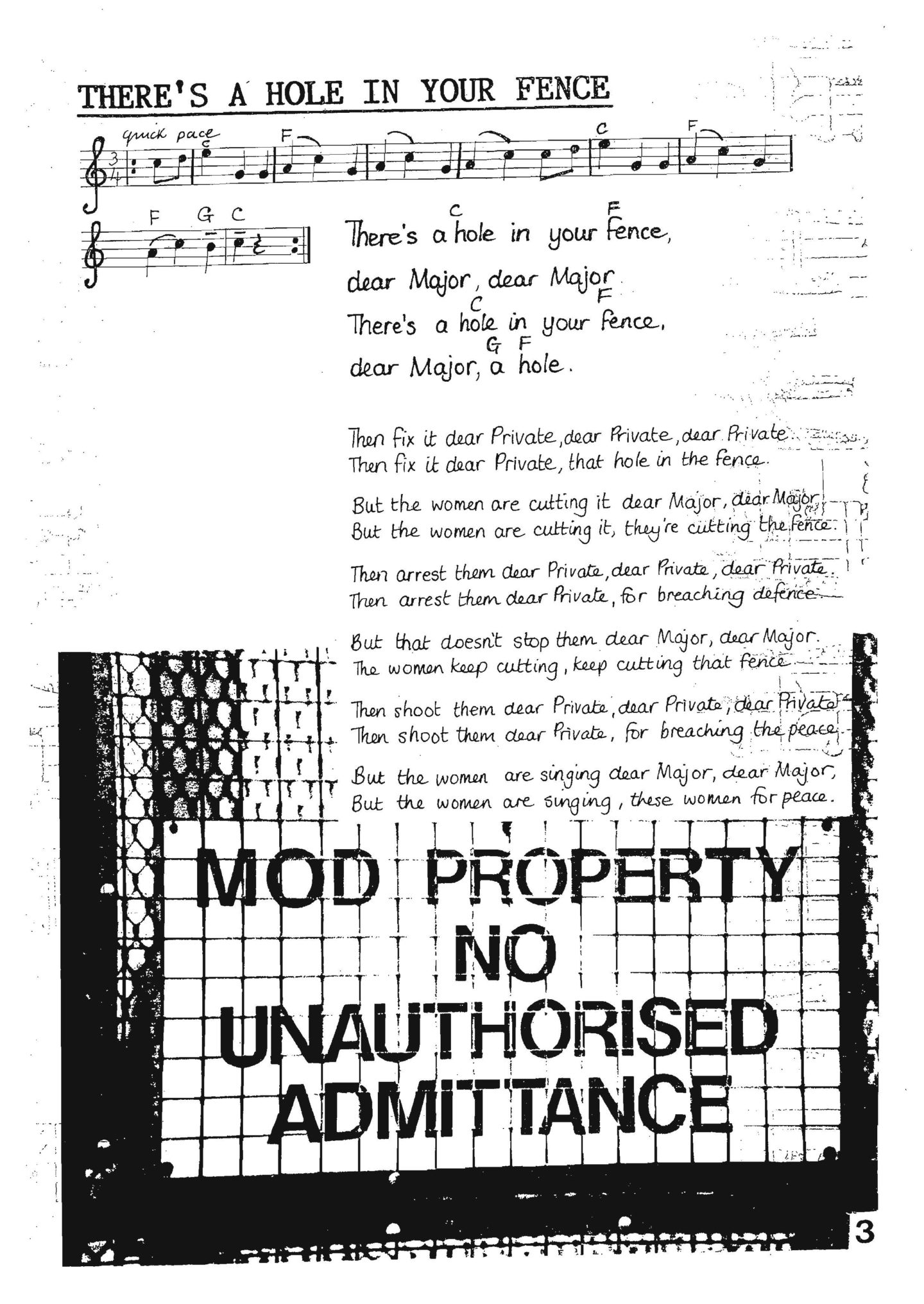

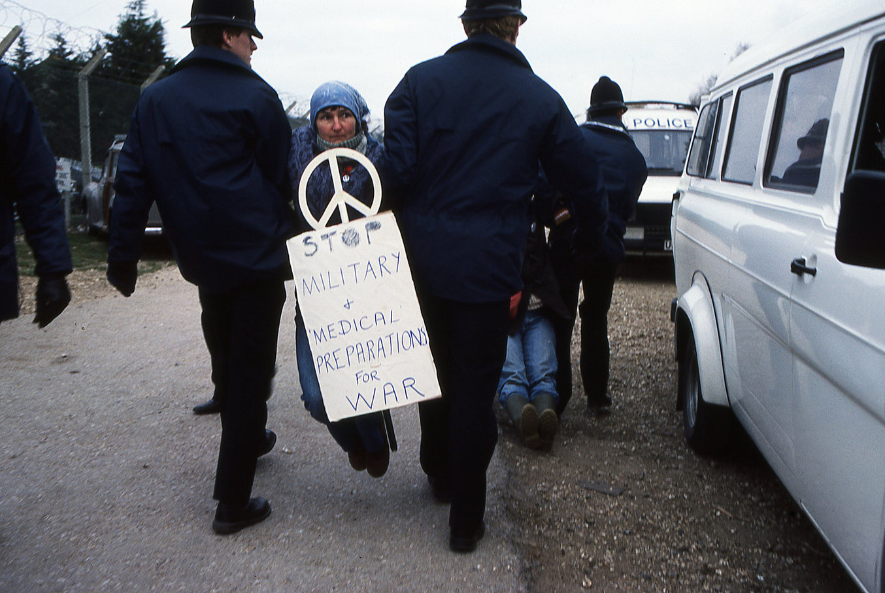

Protests at Greenham Common often took the form of spectacular shows, planned performances and creative activities employing concepts and tools from the field of art. The participants decorated the fence around the base along the entire length with photographs, banners, flowers and ribbons, changing the fence into many kilometres of exhibition space showing anti-war artworks. They also organized masquerades, blockades and body protests lying down on the ground to stop the trucks trying to enter the military base. They dressed as witches and cut through the fence or wore mourning robes and marched in a funeral procession lamenting over the imminent death of children in a nuclear war. In 1980s fences of different bases were ripped open tens of times and many women were arrested for acts of “civil disobedience”.

Arrests occurred on every occasion. For the first time the participants decided to cut the fence of the base on the New Year’s Eve of 1982. Then, they climbed up the silos where they were dancing and singing for an hour. A similar action took place on April 1, 1983 when 200 women dressed as teddy bears symbolizing childhood made a forced entry onto the base grounds despite armed guards trying to stop them. One of the biggest actions called Reflect the Base was organized on December 11, 1983. Fifty thousand women surrounded the base holding mirrors so that the soldiers could see the symbolic reflections of themselves and the things they do. The even ended in hundreds of arrests as the women cut out many large holes in the fence around the base.

In addition to protests, the participants carried out information activities, preparing posters and leaflets which often made use of the spider web image which to them symbolized the persistence and solidarity of the Greenham Common women. They composed their own protest songs and wrote new lyrics for well-known tunes. In 1988, a songbook called the Greenham Women Are Everywhere was published. The originally handwritten book was later typed and photocopied and the proceeds from its sale were spent on the maintenance of the camp. The Peace Camp itself resembled a diligently thought-out artwork. It consisted of nine smaller sub-camps based around the entrance gates to the base which were named after the colours of the rainbow: the Yellow Gate, the Green Gate, the Blue Gate, the Violet Gate etc.

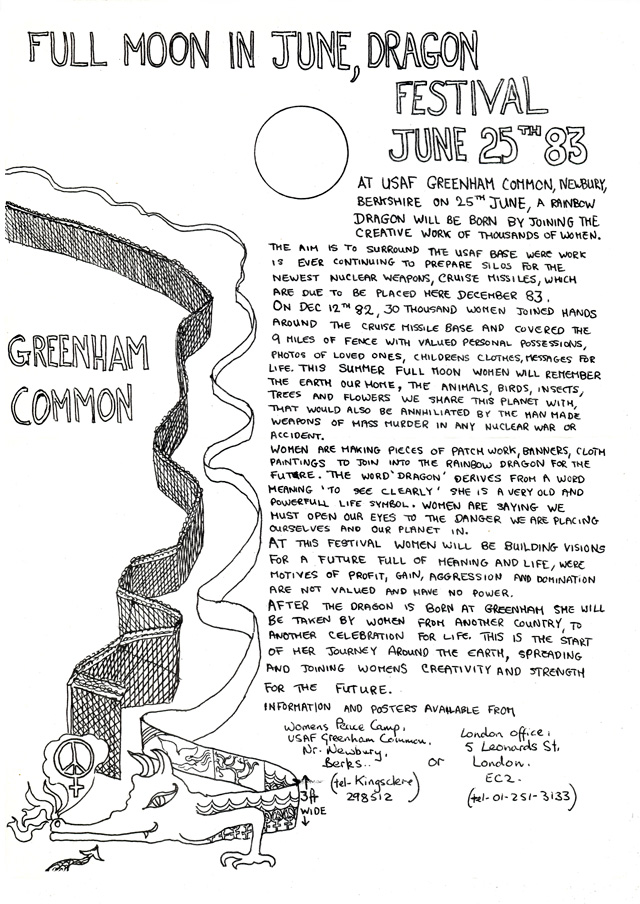

The Peace Camp’s symbol was a female dragon. As the invitation to the Full Moon in June Dragon Festival 1983 explained: “The word »dragon« derives from a word meaning »to see clearly«. She is a very old and powerful life symbol”. Women were invited to join in the celebrations and help with the creation of the Rainbow Dragon.

“At USAF Greenham Common, Newbury, on 25th June a Rainbow Dragon will be born by joining the creative work of thousands of women (…) Women are making pieces of patch work, banners, cloth paintings to join into the Rainbow Dragon for the future”.

Persistence and Memory

The Greenham Common camp hosted from 50,000 to 40 people at different times but it continued to be active non-stop for 19 years. The cruise missiles were removed from the base in March 1991 as a result of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty signed by Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev in 1987 and soon afterwards the base was closed. The camp, however, lasted another 9 years until 200 as part of the protest against the forthcoming UK Trident programme. In 2002, the location of the Women’s Peace Camp was inaugurated as a Commemorative and Historic Site. There are seven standing stones encircling the ‘Flame’ sculpture representing a camp fire. Next to this there is a stone and steel spiral sculpture, engraved with the words “You can’t kill the Spirit” which is the title of the most famous song sung in the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp.

“There weren’t a lot of women’s groups before Greenham, and those that did exist had formal structures, uniforms and captains, organised like the male model. But at Greenham, everyone was equal, and everyone had the opportunity to speak or not speak in a meeting, because there were no leaders. We had a saying: “The only stars are in the sky”. That made it very difficult for the police and politicians to manage; they needed a leader to talk to, but there wasn’t one. They were very frustrated and didn’t know how to react”. Ibidem.↩︎.

“From my point of view it was the best way to live under Margaret Thatcher – to work for peace and live off the meagre dole money. I was about 36 when I arrived and I didn’t leave until eight years later, in May 1990”. Ibidem.↩︎

The photographs come from the website of Pauli Allen, The Danish Peace Academy and the Peace Museum.

The Greenham Common’s song book is available here.