John Heartfield

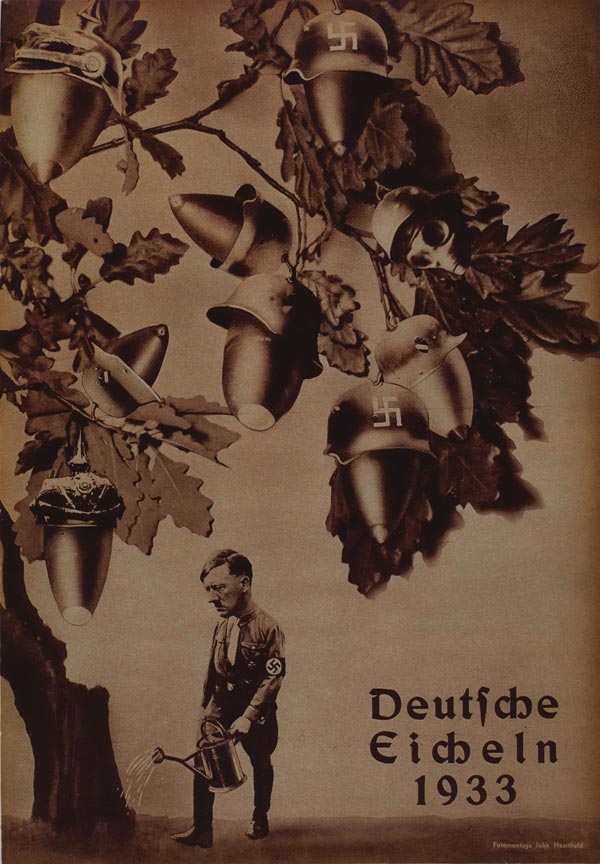

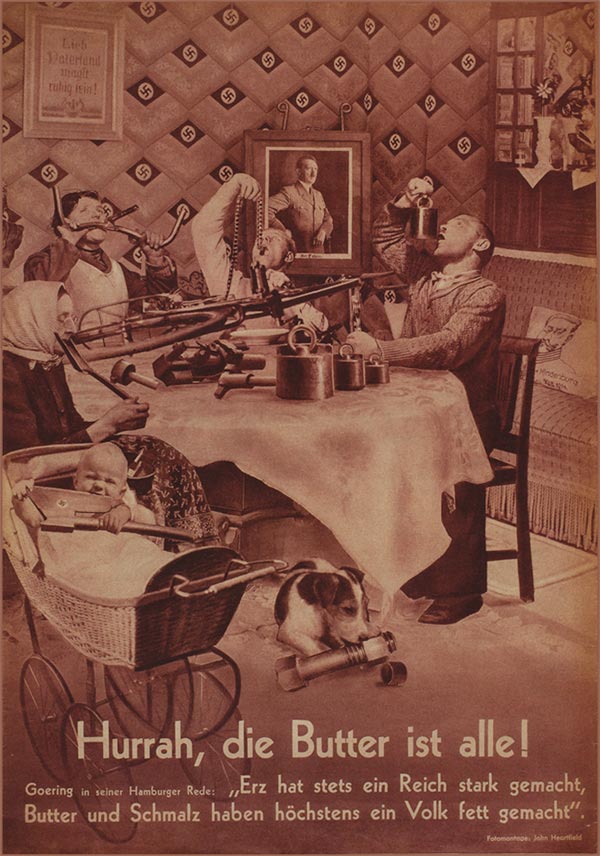

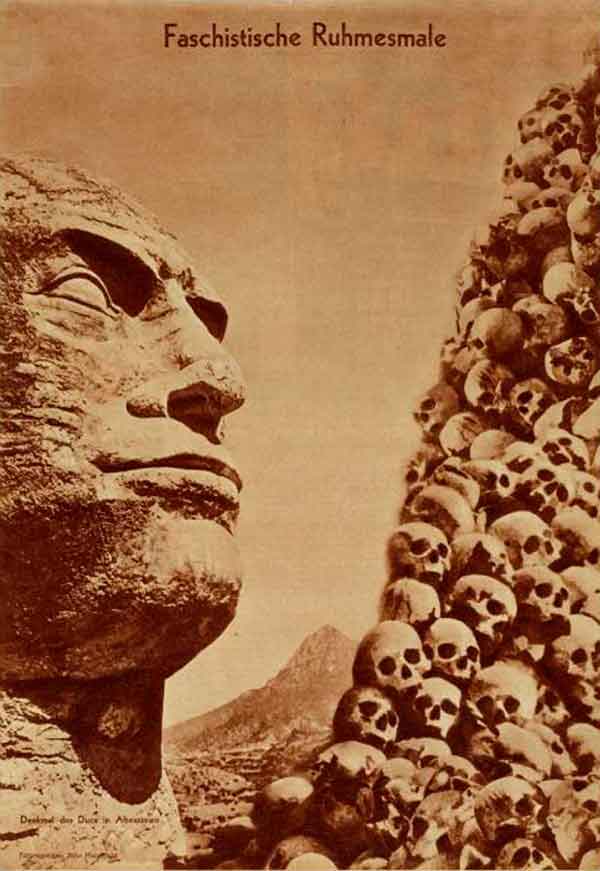

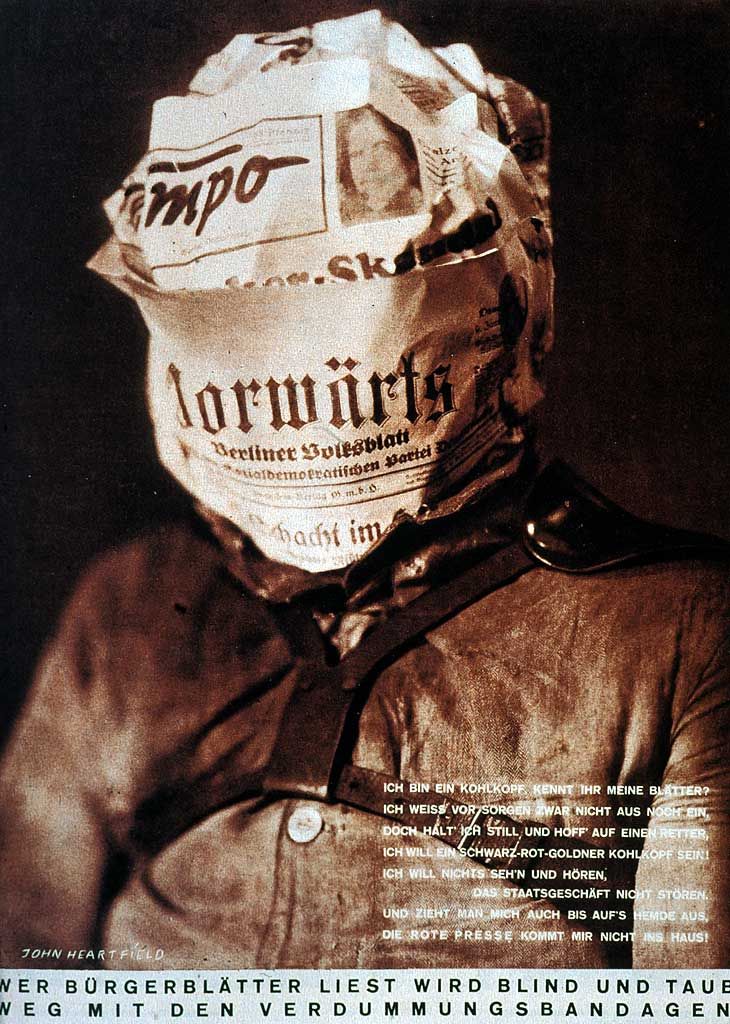

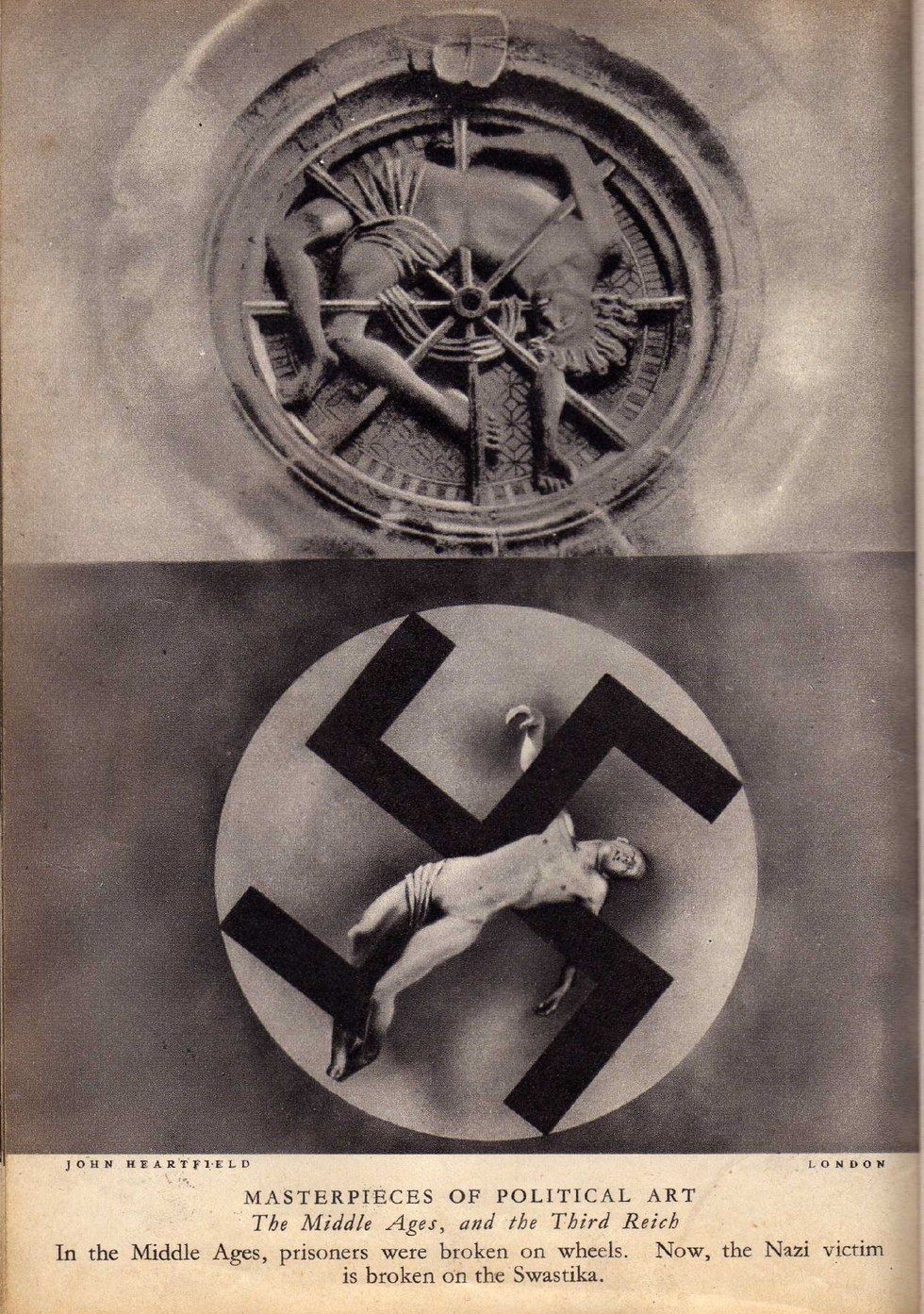

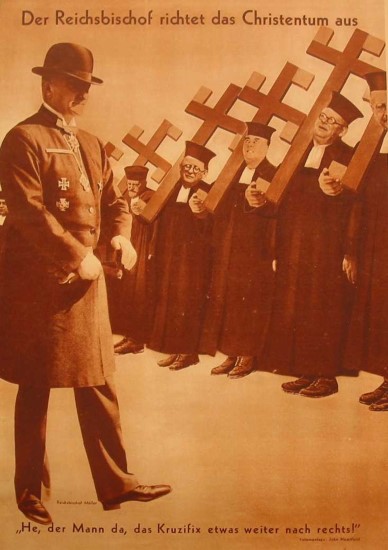

Heartfield’s works were vanguard. In his practice he referred to the ideas of Henri de Saint-Simon who already in 1825 appealed to artists to work for a social change and use art as a machinery to transmit new ideas E. Wolf, A. Zhitomirski, Photomontage as weapon of world war II and the cold war, Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago 2016, s. 72.↩︎ His openly political, anti-war, anti-Nazi and anti-fascist collages were published on the covers of the popular Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (AIZ) issued between 1929 and 1938 by a leftist publisher Willie Münzenberg. The magazine was sold on every street corner at the time when the Nazi party was rising to power, to finally take full control over Germany. Heartfield’s photomontages flooded the visual space as AIZ was one of the three most popular magazines in Germany in the interwar period with a print run of 500 000 copies. Some of the anti-Nazi and anti-war AIZ covers designed by Heartfield were reproduced in the form of posters and put up on Berlin streets to protest against Goebbels’ propaganda. The artist’s works became public warnings against fascism which gained power in the Third Reich. Their visual effect was so powerful that Heartfield earned himself the fifth place on the list of the most wanted drawn up by the Gestapo.

In 1917, Heartfield was hired as a director to make propaganda films for the Press Department of the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The films were supposed to be shown in the countries which took a neutral position towards the war in order to improve the general perception of Germany and attract potential allies. At the time, Heartfield was one of the most promising, young German artists. He just graduated from the Royal Bavarian Arts and Crafts School in Munich and worked as a designer of paper packaging in a large company called Menheim’s Bauer Brothers. He also received a scholarship from the Berlin School of Applied Arts. Heartfield invited two other persons to work with him on the films: another German artist and anti-fascist Georg Grosz who was to take up the role of the art director and his brother Wieland Herzfelde. Aa highlighted by Andres Mario Zervigon in one of his articles, Heartfield’s and Grosz’s ”patriotic” productions were intended to confront the mass audience of civilians and soldiers with the horrors of the war in Europe Andrés Mario Zervigón, A “Political Struwwelpeter”? John Heartfield’s Early Film Animation and the Crisis of Photographic Representation, w New German Critique, New German Critique 107, Vol. 36, No. 2, Summer 2009, s.9.↩︎.But it would be unreasonable to suspect that Heartfield and Grosz, two declared pacifists and anti-fascists, would want to promote Germany’s war machine. Both artists expressed their dissent with the war unanimously and explicitly Zobacz np. Aus einem Interview mit John Heartfi eld: 1967 w Der Schnitt entlang der Zeit. Selbstzeugnisse. Erinnerungen. Interpretationen, pod red. Roldan März, Gertrud Heartfield, Dresden: Verlag der Kunst, 1981, s. 464–69. Heartfield i Grosz przeciw wojnie w Die Kunst ist in Gefahr: Ein Orientierungsversuch 1925, s. 106–24.↩︎. Unfortunately, we can only try to guess what the outcome of their cooperation on the war propaganda films was like, as none of them was ever officially released. The only copies of the films were stolen from Heartfield’s Berlin flat in 1922 and most likely lost for ever.

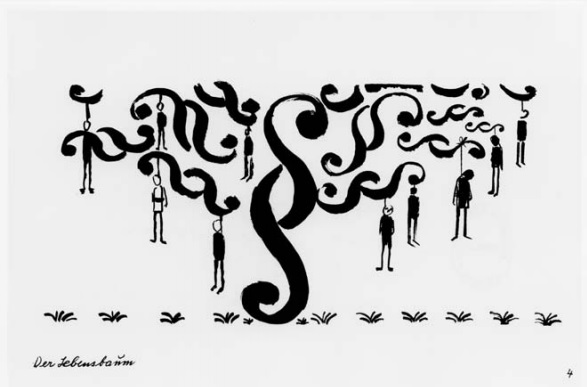

What we know is that Heartfield’s films were to a high extent animated which seems pretty obvious considering his interests in such techniques as the collage and photomontage. He may have come to a conclusion that animation will depict the war atrocities more effectively than acting. Just like his later photomontages, the films were said to have a shocking effect on the viewers, showing the huge ideological and spiritual dissonance in Germany at the time. In the files of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, one can find Heartfield’s letters in which he described ”fantastic grotesque films” he was working on Ibidem, s.10↩︎. Most likely, their titles were Sammy in Europe (a satire on the landing of Americans in France in June and July 1917), The Drawing Hand (an animated narration made up of newspaper news) and A German Soldier’s Song (a feature acted out with puppets which was to resemble Max Reinhardt’s works). Fragments of the storyboards for the films made by Heartfield and Grosz have been preserved. One of the drawings shows a tree which consists of paragraph signs normally used in official regulations or army documents. In this case, dead bodies are hung on the paragraphs.

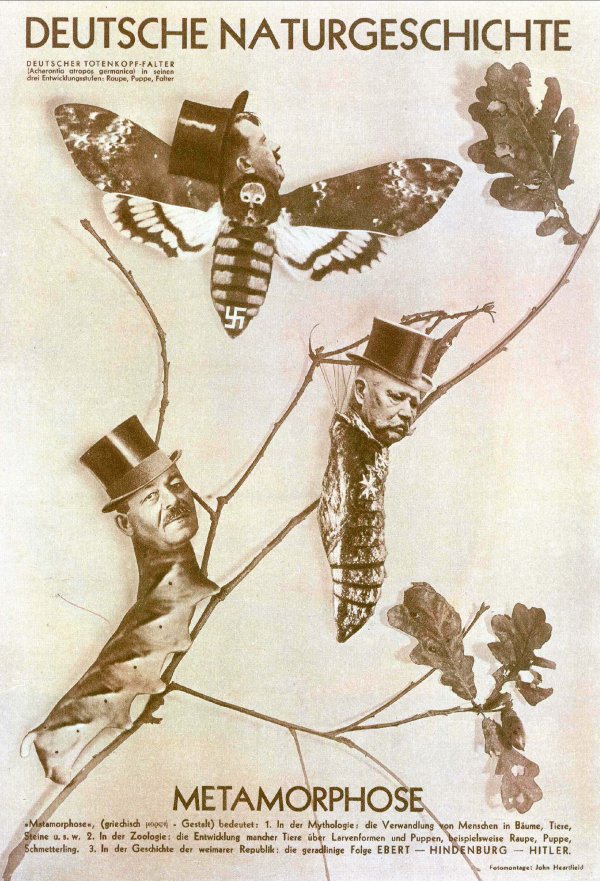

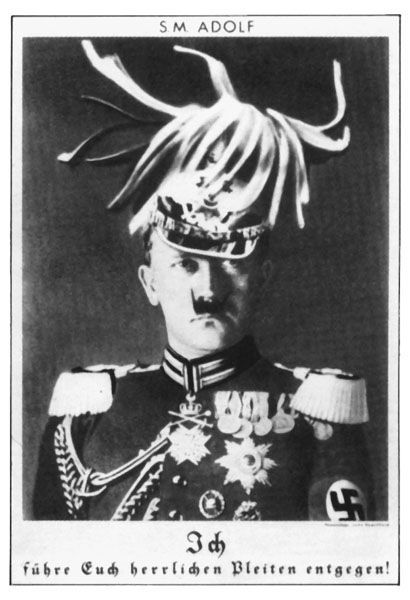

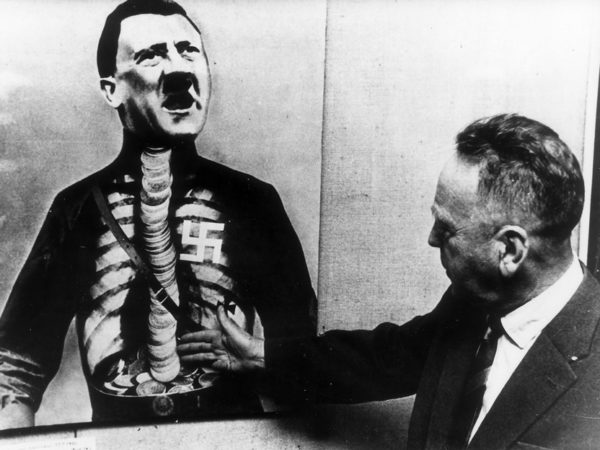

Some of the cartoons or puppet movies were based on German traditional stories for children, such as the Struwwelpeter, a popular 19th century tale. In this story, children who misbehave are punished in a very cruel way. For instance, the Shaggy Peter accidentally loses his fingers. Based on the fairy tale, a satire called Der politische Struwwelpeter was created in 1849 showing the cacophony of political attitudes and voices presented as a multi-headed hydra with heads of various politicians and church officials growing out of one body. The idea occupied Heartfield’s imagination for quite a long time. In 1932 he created an anti-Nazi photomontage showing Hitler in two military uniforms as a hybrid made up of two different bodies. In 1920s and 1930s Heartfield became well-known for the explicit satirical tone of his visual works, sharp and merciless just like the 19th century German folk tales. The drawings made in preparation for the films were so good that the Ministry decided to print them in the form of a series of posters and postcards.

Heartfield and Grosz also worked on their own dada paintings and photographs. As Wieland Herzfelde, Helmut-John’s brother, recollected years later, they sent together subversive, photomontage postcards to the war front. In those small pictures, pieces of photographs were arranged in a way which clearly showed what the censors removed W. Herzfelde, John Heartfield: Leben und Werk, Dresden: VEB Verlag der Kunst, 1976, s. 17.↩︎. In their works, Heartfield and Grosz presented elements of the German war propaganda, sometimes literally instructing the astonished audience how to deconstruct the German official narration based on overindulgent patriotism.

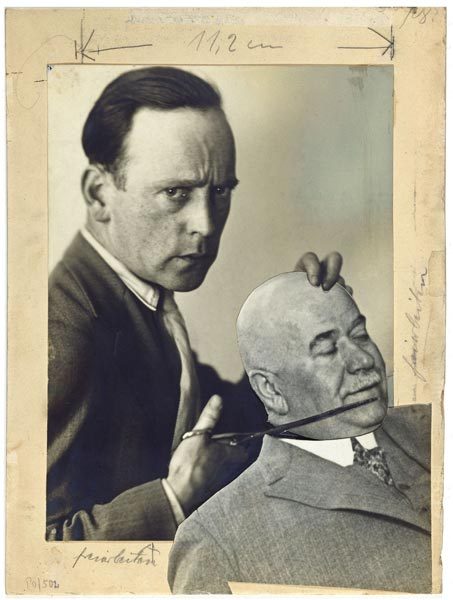

The first of Heartfield’s works was published in Arbeiter-Illustrierte-Zeitung (AIZ) in September of 1929, in the magazine’s issue no. 37. The collage shows Heartfield himself in the act of decapitating Karl Zörgiebel, the Chief Constable of Berlin’s police, using large scissors. The work refers to the events of May 1929 (known as the Bloody May) when a peace demonstration of workers was violently suppressed by the police. In her book on Heartfield, Sabine Kriebel, an art historian, points out that:

“Heartfield’s collage not only gives the social fascist a face but also thematizes the fight against him; […]. In the form of popular politics, the righteous photomonteur Heartfield dispenses justice on behalf of the radical Left, avenging the dead, injured, imprisoned, and politically dispossessed (…)” S. Kriebel, Manufacturing Discontent: John Heartfield’s Mass Medium, w New German Critique 107, Vol. 36, No. 2, Summer 2009 s. 56.↩︎.

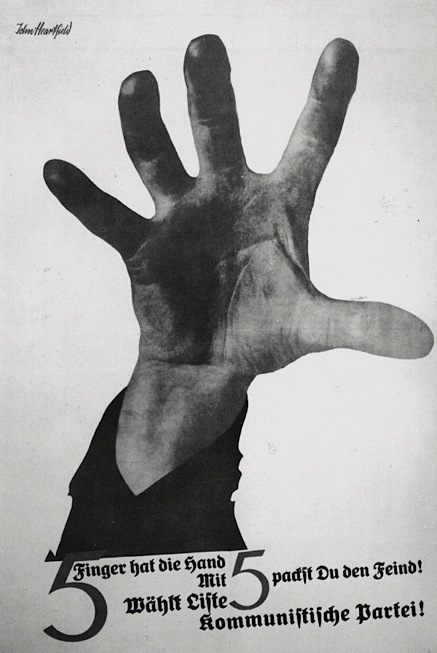

One of Heartfield’s famous slogans was “Use photography as a weapon”. Since AIZ was the second most popular illustrated magazine in Germany and had millions of readers the artist could test the effectiveness of his montages as a revolutionary weapon with a mass range. Heartfield’s photomontages labored to stimulate political consciousness through compelling visual means during a period of extreme political and social upheaval. The ultimate goal was to create a community of revolutionary-minded citizens who would actively contribute to radical social change. Heartfield’s subsequent involvement with Berlin Dada, whose art and actions were provoked by the traumatic war and the failed revolution of 1918–19, was an antibourgeois, prorevolutionary protest that mobilized photomontage as a political weapon, representing the Weimar Republic as a disorderly verbal-visual cacophony. Although the radical proclivities of the Dadaists waned in the mid-1920s, Heartfield remained, for better or worse, a dedicated agitator for the communist cause, designing election posters, book jackets, and, beginning in 1929, satirical photomontages for the AIZ.

Heartfield’s degradation from a recognized communist artist to a political pariah chased by the Gestapo reflected the political changes taking place in Germany in 1930s and 1940s. He was badly beaten a couple of times by Hitler’s supporters who thought his works mocked their idol and once even thrown from a moving streetcar. In April 1933, a few months after Hitler was named the Chancellor of Germany, Heartfield had to flee Berlin. The artist narrowly escaped when an SS squad broke into his apartment a few days later, right on Good Friday. Heartfield jumped from his balcony and for seven hours crouched hidden in a metal bin.

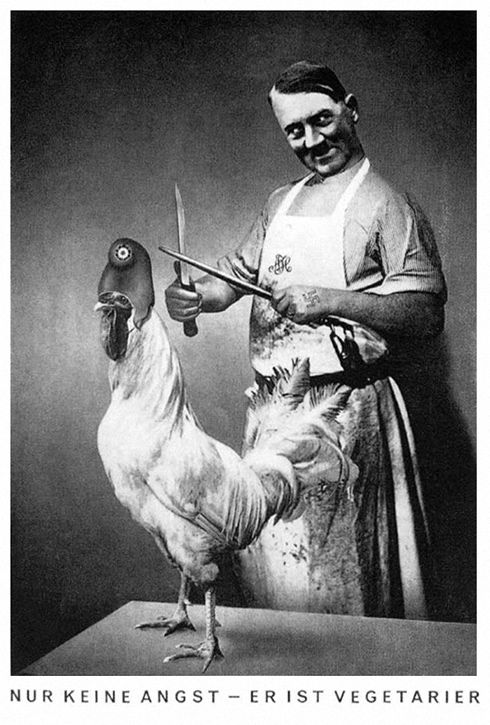

Heartfield continued to create his anti-war and anti-Nazi art in Prague until Hitler invaded and occupied part of Czechoslovakia in 1938. Before that time, the artist stayed in Prague where, together with other communists in exile, he kept producing drawings for AIZ becoming the unquestionable leader of the anti-Nazi propaganda. In 1934, he took part in the International Exhibition of Caricature organized by the Manes Art Association where, among other works, he showed caricatures of Hitler and Piłsudski. The episode ended in a widely publicised police intervention and removal of five of Heartfield’s works from the exhibition. A week after the exhibit opened in April 1934, the German envoy to Prague, Walter Koch, dispatched an official protest to the Czech Foreign Office over what he considered defamations of Hitler, other German statesmen, and German political symbols in a well-trafficked area in the middle of Prague. Koch requested that the Czech Foreign Office remove the offending images immediately. Krofta asked the exhibitors to remove Heartfield’s Adolf the Übermensch—not entirely from the exhibition but from the display window visible from the street. The montage was replaced by caricatures of Stalin, the Austrian chancellor Dollfuß, and Czech politicians. But that did not put an end to the dispute and soon afterwards Heartfield’s works were withdrawn from the exhibition.

John Heartfield survived the Second World War in England where he was granted asylum as a Jewish refugee. The war took a heavy physical and psychological toll on Heartfield. Due to his neurological condition he was unable to continue his artistic activity. In 1950, he returned to the Democratic Republic of Germany where he had difficulties with finding a job. On the one hand, this was caused by the emergence of a new visual language under the influence of the Soviet Union and attacks from Georg Lukacs on the modern literature and art (the Marxist philosopher criticized expressionism, montages and all modernist manifestations of art as too distant from the lives of common people). On the other hand, Heartfield’s contact with pre-war German communists executed during the times of the Great Terror made Heartfield a suspicious persona in the eyes of the Stalinist authorities. As he was refused membership in the party, he could not join the GDR Association of Visual Artists which, in turn, meant that he could not teach, exhibit his works or work as a designer. Heartfield’s situation changed only after Stalin’s death in 1953 when he regained his status of one of the most significant artists in East Germany, mostly thanks to the journalists and writers with whom he worked closely before WW2. In 1956 he became a member of the Central Committee’s Board of Designers of Poster Agitation and Propaganda of the Socialist Unity Part. One of the last exhibitions in which Heartfield participated in his life was held in 1957 in the Municipal Library in Berlin.

By operating with and through photography, Heartfield used the medium’s powerful visual fidelity not for its attentiveness to surface appearances but for the real. In this way he was looking for “interpretations offered by the reality”, as Rosalind Krauss, American art theoretician put it R. Krauss, Photography in the Service of Surrealism, w Photography and Surrealism, red. Jane Livingston New York: Abbeville, 1985, s. 25.↩︎. Heartfield’s works make use of sensual lavishness, create noise and evoke pain or even a scream like in the photomontage in which the artists cuts off the head of Karl Zörgiebel or the one with text spewing from Hermann Göring’s head as this newer political Struwwelpeter issues pointless curses before the towering Georgi Dimitrov, a communist activist accused of the attempt to set the Reichstag on fire in 1933.

In his works created for AIZ, Heartfield tried to eliminate any traces of artistic intervention and blend all visible joints . To this end he pressed the photomontages between heavy glass panels and later meticulously retouched the works. Heartfield’s medium – cut out and precisely pasted pieces of photographs and texts – represented a vivid intervention into the mass visual culture which at that time relied almost entirely on photographic images. The technological progress which made it possible to print text and pictures together at high speed had a huge influence on the revival of the publishing industry in 1920s. Photographs considered as one of the main sources of information appeared everywhere – in books, newspapers, posters, advertisements and billboards. The whole new industry of illustrated magazines emerged and AIZ was one of them.

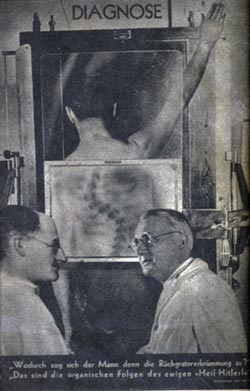

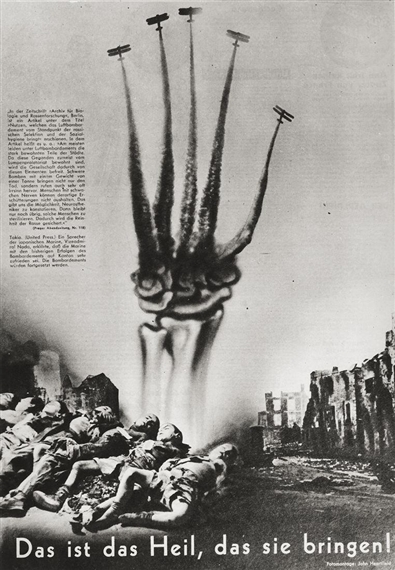

Heartfield’s photomontages usually refer to specific political events, like for instance the work entitled Das ist das Heil, das sie bringen! (This is the Salvation They Bring Us!) of 1938 which is a comment on an article published in a German periodical Archiv für Biologie und Rassenforschung in which the author, in line with the Nazi logic, the author excuses the bombing of Spanish cities during the Civil War in Spain saying that the densely populated sections of cities which suffered most acutely in air raids were areas inhabited for the most part by the ragged proletariat, so their death could contribute to the maintenance of the purity of the race. In the photomontage, Heartfield made use of pictures of aircrafts which put together form a hand of a skeleton to symbolize the real goal of the seemingly harmless aerial stunts. The work also draws on a pun on the German greeting Heil Hitler! in which the word Heil means both salutation and salvation. Heartfield shows very clearly what kind of ‘salvation’ is offered by the Nazis killing thousands of innocent civilians.

The shock evoked by Heartfield’s dada photomontages has retained its power until nowadays, showing the political and everyday reality of the Weimer Republic. The visual provocations activate our senses using the dada aesthetics and, unfortunately, still remain surprisingly up-to-date.