Karl Schwesig

Karl Schwesig was born on 18 June 1898 in Geisenkirchen, a small town in the Rurh District in a working class family. As a child, due to the poor living conditions and long-term malnourishment he developed rickets, a disease with the consequences of which he struggled all his life. But his small height and poor health saved him from death during World War I when instead of being sent to the frontline he did his military service working in an office of a nearby mine. In 1918, having completed a three-year service period, he started studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Düsseldorf, a city where he ultimately settled down and developed his artistic and political career.

Mother Ey and her Düsseldorf avant-garde

The Düsseldorf Academy did not turn out to be a friendly place for Schwesig. After two years he quit the conservative school and joined a group of artists gathered around Johanna Ey, a gallery owner, art collector and dealer known as “a woman whose portraits were painted more often than that of any other woman in Germany”. In 1907, Ey (affectionately named Mother Ey), opened a bakery and cafe near the Academy which quickly became a meeting place of students and local avant-garde artists. As most of the customers were usually in financial distress, they chose to pay their bills with works of art. In this way, already in 1920s Ey had a large collection of modern art pieces and quickly became a legend of the local world of art and press. She was the one who actually animated the Düsseldorf art scene and was respected so much that when she had trouble with finding a place for her gallery, she received from the city new premises, free of any rent – in the building of a former post office where she operated her successful gallery until 1934.

In 1919, the artists under the care of Ey formed a group called Das Junge Rheinland (The Young Rhineland) which at the time of its highest popularity attracted more than 400 artists dealing with poetry, theatre, architecture and fine arts. The most famous Young Rhinelanders included Max Ernst, Otto Dix, Wilhelm Kreis, Adolph Uzarski, Marta Worringer and Arno Breker https://www.kunstpalast.de/en/museum-3/Exhibitions/current-2/too-good-to-be-true.↩︎. As part of its activities, the group was publishing a magazine to promote new trends in art and to enable contacts between artistic circles from all over Europe. What united the members of the group in terms of style was a radical rejection of academic art; the Young Rhinelanders agreed on one thing – art after World War I must change because the canon known from schools of fine arts did not fit in with contemporary life. At the end of the 1920s, Das Junge Rheinland, together with other groups who are co-creators of Düsseldorf’s artistic milieu, united in the Rheinischen Sezession (Rhineland Secession) and formed a very broad and diverse front promoting progressive art.

The events of the first half of the 1930s (including, above all, the collapse of the Weimar Republic and Hitler’s rise to power) have radically cut short the activities of the creative community in Düsseldorf. In 1933, Das Junge Rheinland was outlawed by the Nazi authorities, who considered the group to be the mother of degenerate art, despite the fact that some of its former members and members who showed sympathy for the new government became accepted artists in the Third Reich. The Rheinischen Sezession itself was dissolved by a 1938 decree, as an organization bearing traces of the “degeneration” of Johanna Ey’s time. The creators and creators, considered “degenerate”, shared the fate of other progressive creative circles in Germany at the time and were banned from artistic activity. Their works of art were taken away from authors and collectors – some of them were destroyed in the show performances of the authorities, while the rest were dearly sold.

Left wing

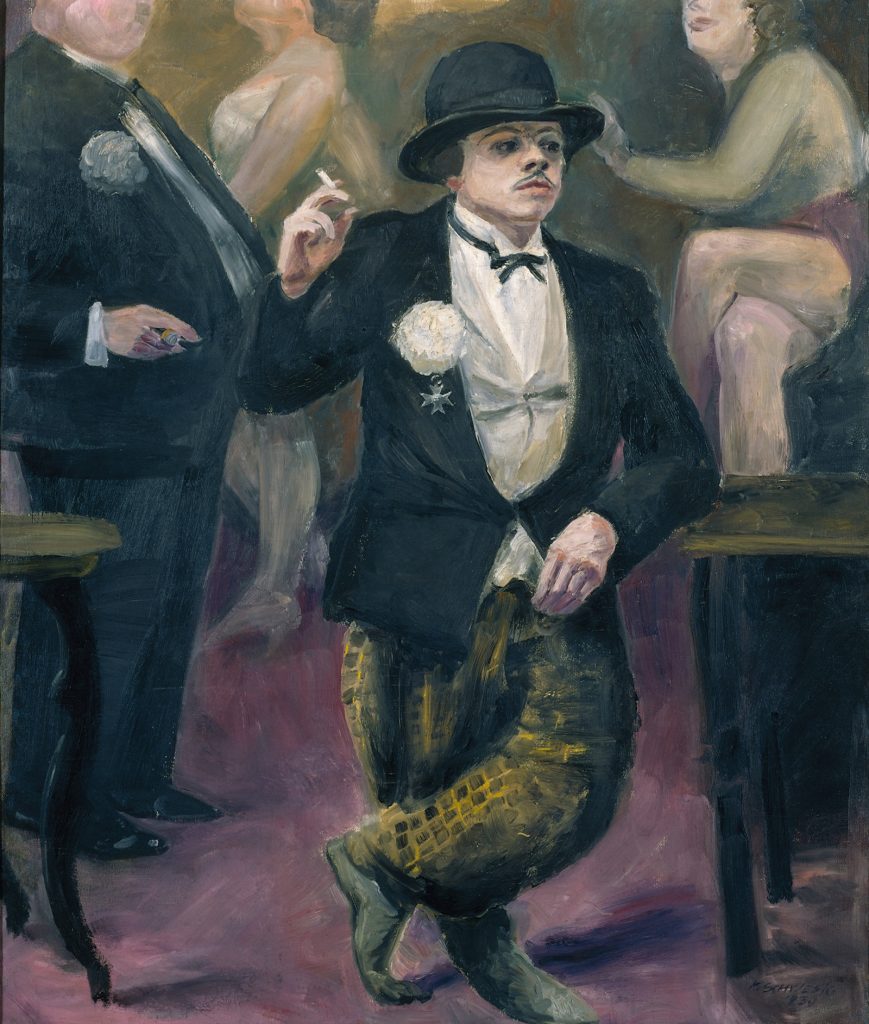

In 1921, Karl Schwesig tied his future to Mutter Ey. In addition to the avant-garde forms, the artist wanted an equally avant-garde content – he was a declared communist and an opponent of war. Together with Peter Ludwigs and Gert Heinrich Wollheim, painters who had already been acquainted with the Academy, they founded “Die Peitsche”, a left-wing satirical-political magazine, in 1924. Like many other initiatives of this kind in the Weimar Republic, “Die Peitsche” was also full of satirical texts and drawings in which the artists critically commented on progressive militarism, social stratification and bourgeois hypocrisy. In the same year 1921, a group of friends took part in two exhibitions of a clearly pro-social character – “Der Kampf” in the Kunsthalle in Düsseldorf and “Der Ersten Allgemeinen Kunstausstellung” in Moscow, together with Käthe Kollwitz and Otto Dix, among others. Their career was, of course, facilitated by their acquaintance with Johanna Ey.

In 1929, on the wave of popularity that the Berlin-based ASSO (Assoziation revolutionärer bildender Künstler), the Association of Revolutionary Visual Artists, was gaining, Schwesig together with Ludwigs, Wollheim and other left-wing artists and intellectuals from Düsseldorf founded a local branch of the association. Numerous initiatives have been launched in the Rhineland ASSO, including the agitated-propaganda revolutionary theatre Nordwest-ran under the direction of Wolfgang Langhoff. Among others, the Afro-German amateur actor Hilarius Gilges, who is also known as an exceptionally effective agitator, made his debut at Nordwest-ran.

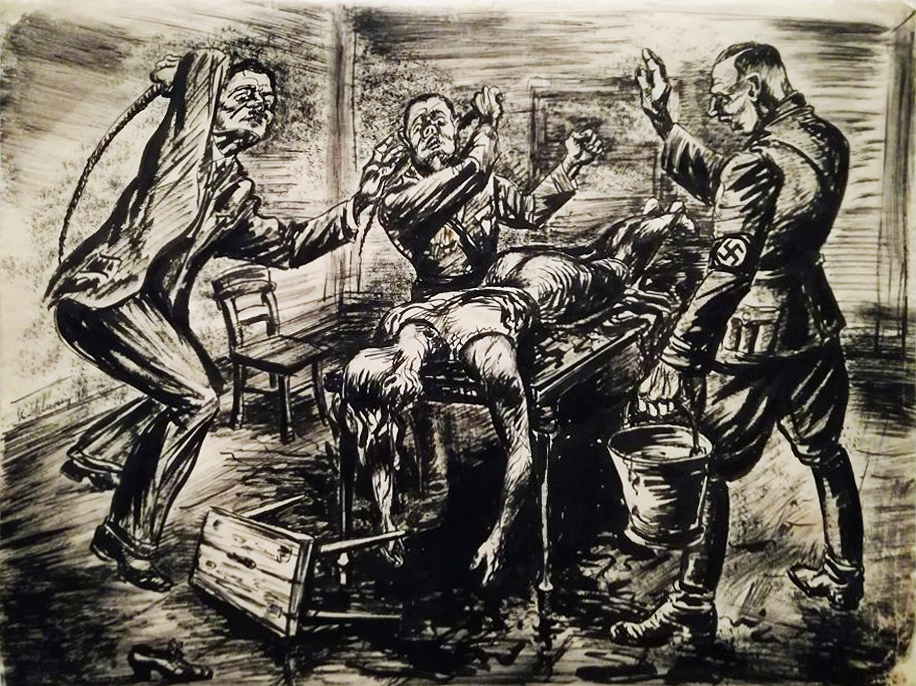

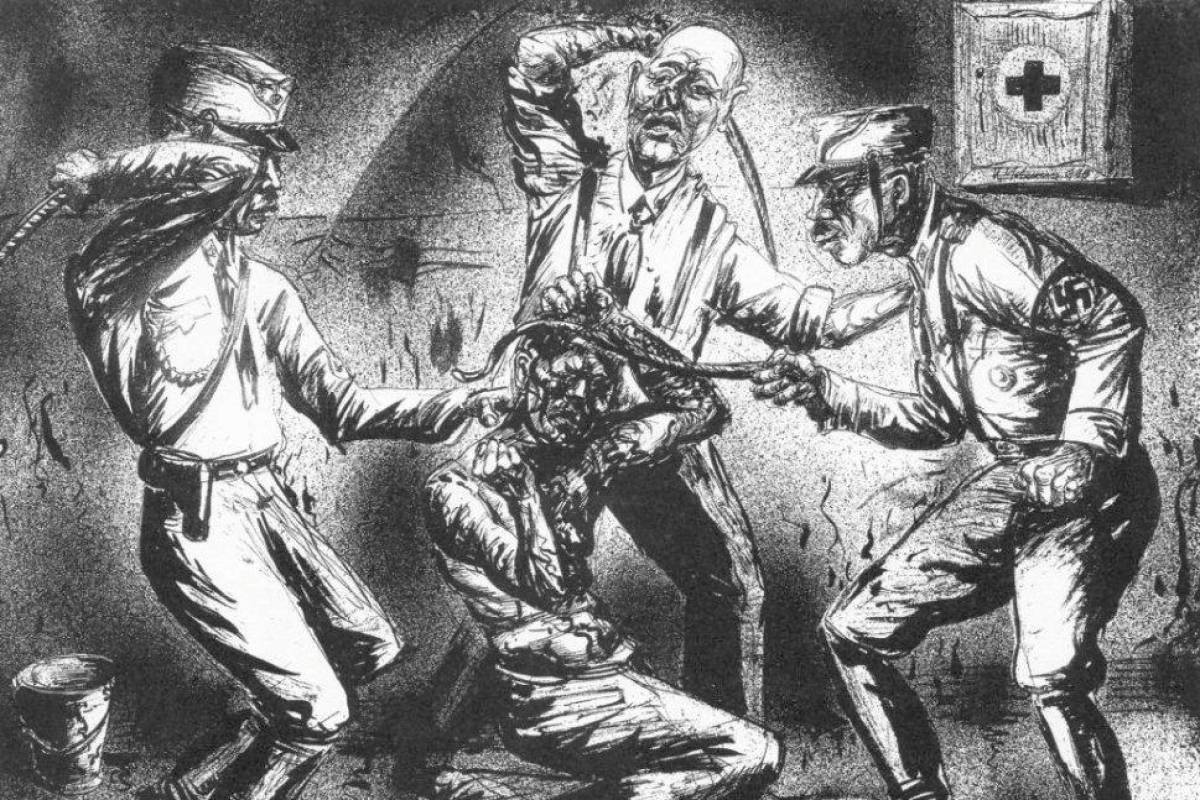

In 1933, with the takeover of power by the NSDAP and the collapse of the Weimar Republic, the Düsseldorf milieu of left-wing intellectuals and artists became the target of surveillance and later of massive attacks by the new government. In particular, Schwesig, as an open opponent of Nazism and an animator of left-wing culture in the city, who was additionally engaged in helping those persecuted after the events related to the arson of the Reichstag, was considered one of the most important local enemies of the Third Reich. As early as July 11, 1933, Schwesig was arrested by the NSDAP Assault Troops (SA). For several days he was subjected to constant torture as a person accused of treason and preparing resistance against the Nazis. Afterwards, he was imprisoned in Wuppertal.

Other members of the Düsseldorf ASSO community also suffered repression – Langhoff and Hanns Kralik were arrested, among others, and the black Hilarius Gilges was brutally murdered. Schwesig’s friend Peter Ludwigs, though constantly under Gestapo surveillance, organized with Otto Pankok in Düsseldorf a circle of anti-fascist artists active in the resistance movement, which supported materially persecuted artists and imprisoned leftists. Most of the artists from the Düsseldorf circle managed to escape from the Third Reich and survive the war. Julo Levin, an expressionist of Jewish descent who died in Auschwitz, who was associated with Szczecin was not lucky enough to do so.

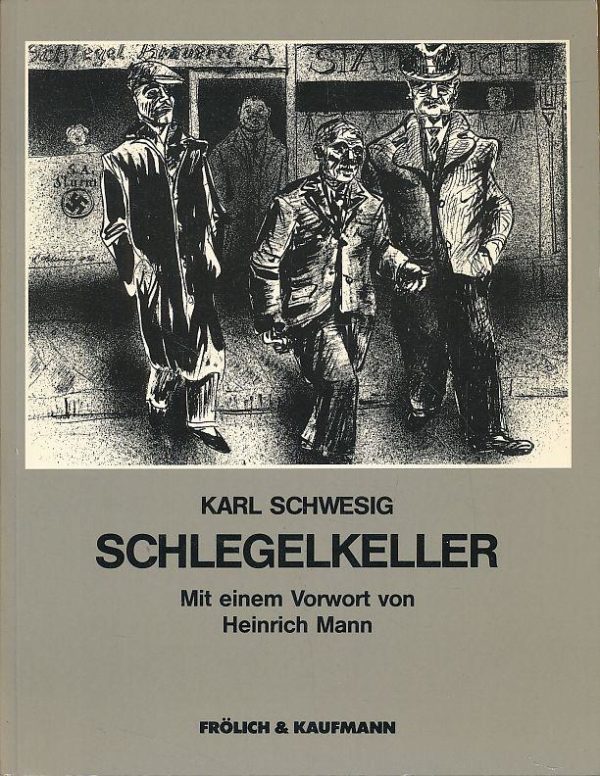

A beautiful story about cruelty or Schlegelkeller

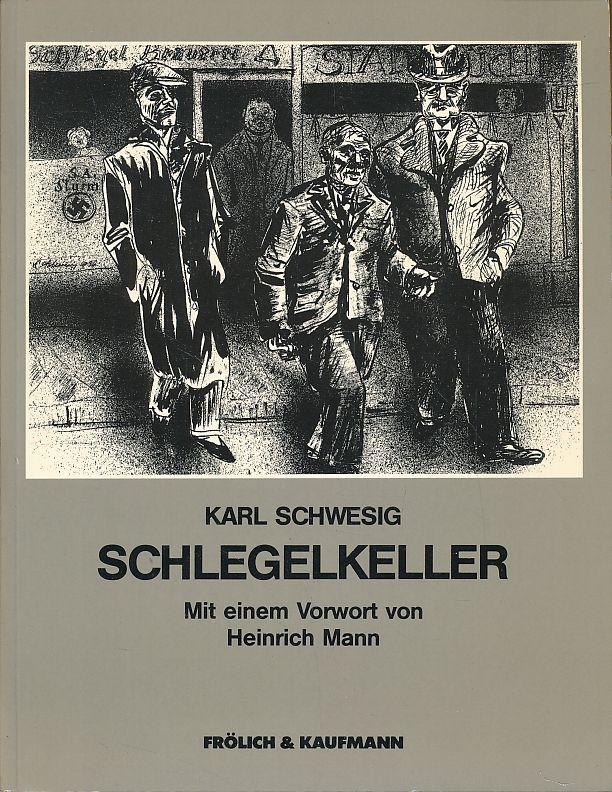

In the absence of evidence, Schwesig was released in November 1934, after sixteen months in prison, but the artist was still under constant police supervision as a person openly opposed to Nazism. Schwesig immediately began working on his diary from prison. In the spring of 1935 he managed to escape to Belgium, where he received political asylum. There he continued to work on his life’s work – the initially modest diary quickly turned into a richly illustrated testimony against the Third Reich. The Schlegelkeller series (consisting of memoirs and about 50 ink drawings suggestively depicting the brutality of the SA against political opponents and minorities) was completed by Schwesig in 1936, perfectly aware of the strength of his work. Moreover, illustrating the memories was the execution of a cynical order given to the artist by one of the SA officers:

Take a good look at it so that you can later paint a beautiful story about cruelty The original text ”Sieh dir das genau an, damit du später mal ein schönes greuelmärchen malen kannst” quoted from: K. Schwesig, Schlegelkeller, Düsseldorf 1983, p. 146.↩︎.

For the written and illustrated memories to play their part, they had to be staged – Schwesig wanted them to be a clear warning against the indulgent treatment of Hitler by Europe at the time. Eventually, before the war, the Schlegelkeller series was presented three times – in 1936 in Brussels and Amsterdam and in 1937 in Moscow. In 1939, it was proposed that part of the cycle be reprinted by the American magazine “TIME” – as a clear testimony of Nazi crimes committed before the start of World War II, but for unknown reasons the publisher finally refused to publish it.

In 1940, with Hitler’s troops entering Belgium, Schwesig was captured and deported to the south of France where he was held in the camps there. Three years later, the artist was taken to the Reich under escort of the Gestapo, where he was further interned. Schwesig was released from prison in 1945, shortly before the capitulation of the Third Reich. He spent the last decade of his life in his beloved Düsseldorf, taking part in rebuilding cultural life after the Second World War disaster. Before his death in 1955, the artist returned to the motifs of his memories of internment and Nazi executioners in his creative work.

In 1983, on the initiative of the Remmert und Barth gallery in Düsseldorf, the Schlegelkeller album with a preface by Heinrich Mann was published.