The Freedom Ride

On May 4, 1961 a group of activists from the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) set off on a Freedom Ride heading for the south of the United States. Their destination was New Orleans were the group planned to arrive on May 17. The event was planned and organized by CORE in commemoration of the seventh anniversary of the so called Brown decision, a landmark decision for the gradual abolition of the racial segregation in the United States. On May 17, 1954 the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that racial segregation in American public schools was unconstitutional and violated the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. Six years later, in December 1960, the Boynton vs. Virginia case overturned a judgment convicting an African American law student for trespassing by being in a restaurant in a bus terminal which was “whites only” ruling that racial segregation in public transport between states was also unconstitutional.

The Freedom Ride strategy was to repeat the famous action of 1947 called the Journey of Reconcilation. At the end of 1940s, sixteen CORE activists set off on a journey heading south with an aim to challenge the rule of racial segregation on interstate public transport. Over the period of two weeks white persons took the seats reserved for black passengers and black activists occupied the seats reserved for white people. In the course of the campaign the protesters got arrested a number of times, particularly in North Carolina, however, with time the action made an impact as it highlighted the unconstitutional nature of racial segregation.

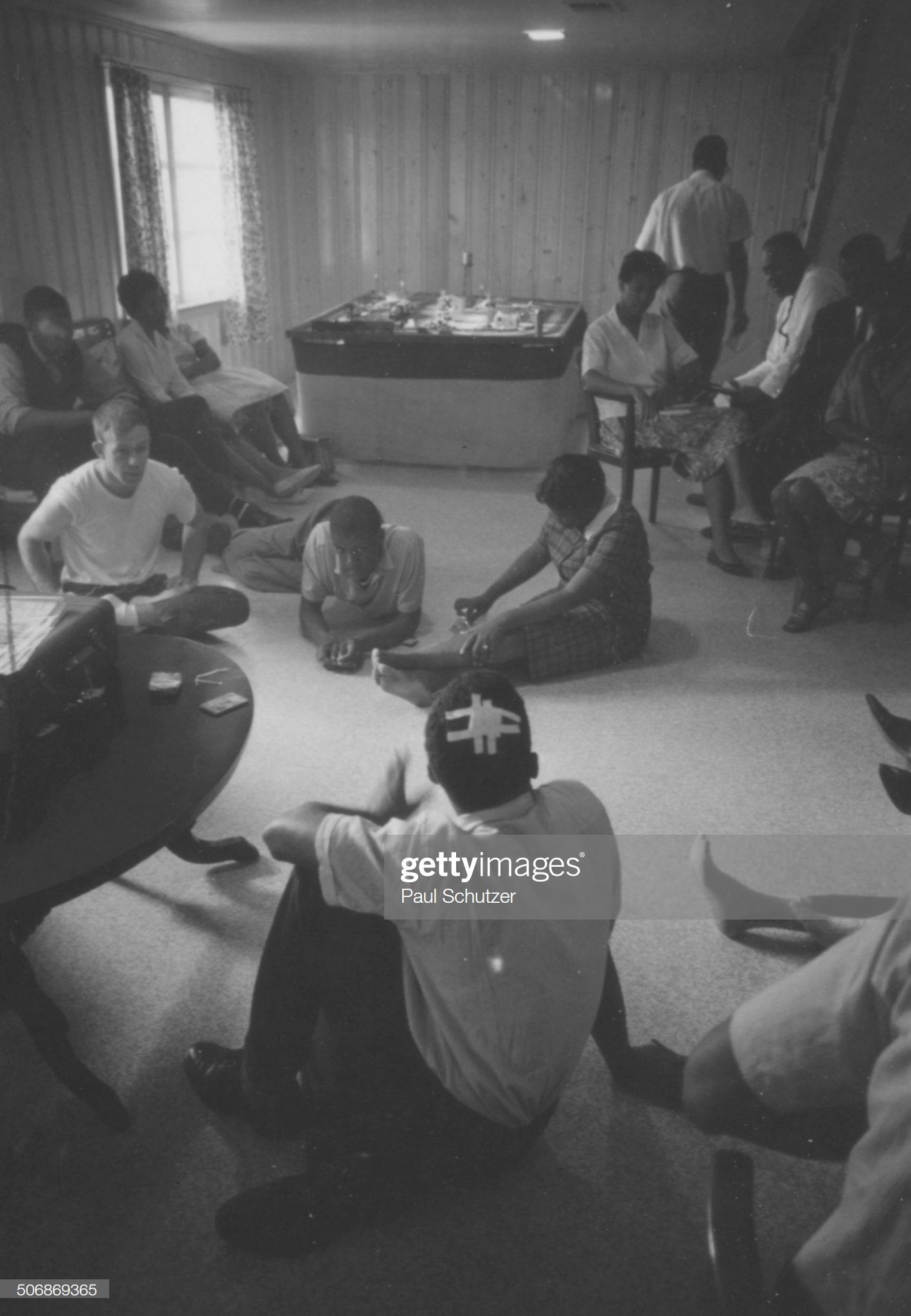

In 1961, CORE activists who were planning The Freedom Ride knew very well that the southern states were still sticking to the old racist rules of managing public space. As part of the action, groups of black activists not only took the seats reserved for white people, but also entered the waiting rooms and bus stop zones still marked with “Whites only” signs. The white activists, on the other hand, appeared in places which were meant for Afro-Americans following the as if approach – “as if racial segregation never existed”.

James Farmer, the leader of CORE at the time and an active participant of the action recollects:

”When we began the ride we had been told by social scientists and by activists in the south that we could anticipate violence. We might even face death”.

Farmer did not want to call the protest an act of ”civil disobedience” because, as he put it” because we would be doing merely what the Supreme Court said we had a right to do”. In his opinion, The Freedom Ride was an activist provocation.

”We felt that we could then count upon the racists of the south to create a crisis, so that the federal government would be compelled to enforce federal law.”

On May 14, when travelling through Alabama the activists split into two groups. The first one was attacked in Anniston. Nearly 200 people stopped the bus on the road. Stones were thrown at the bus. the tires were punctured and finally the vehicle was set on fire. The other group passing through Birmingham was attacked by the local population and badly beaten. The police did not react to violence although, as the subsequent investigation proved, the FBI had known about the planned attack inspired by the local Ku-Klux-Klan members. The police was specifically ordered not to intervene. John Patterson, the Governor of Alabama, offered no apologies explaining that:

“When you go somewhere looking for trouble, you usually find it… You just can’t guarantee the safety of a fool and that’s what these folks are, just fools”.

Despite the initial setbacks and problems with bus companies and drivers, the activists decided to continue their trip. The events in Anniston and Birmingham, combined with the non-action of the police, negligence of the state authorities, the growing engagement of anti-racist groups from other cities, arrests of the activists and personal involvement of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy finally brought the awaited publicity and tangible effects.

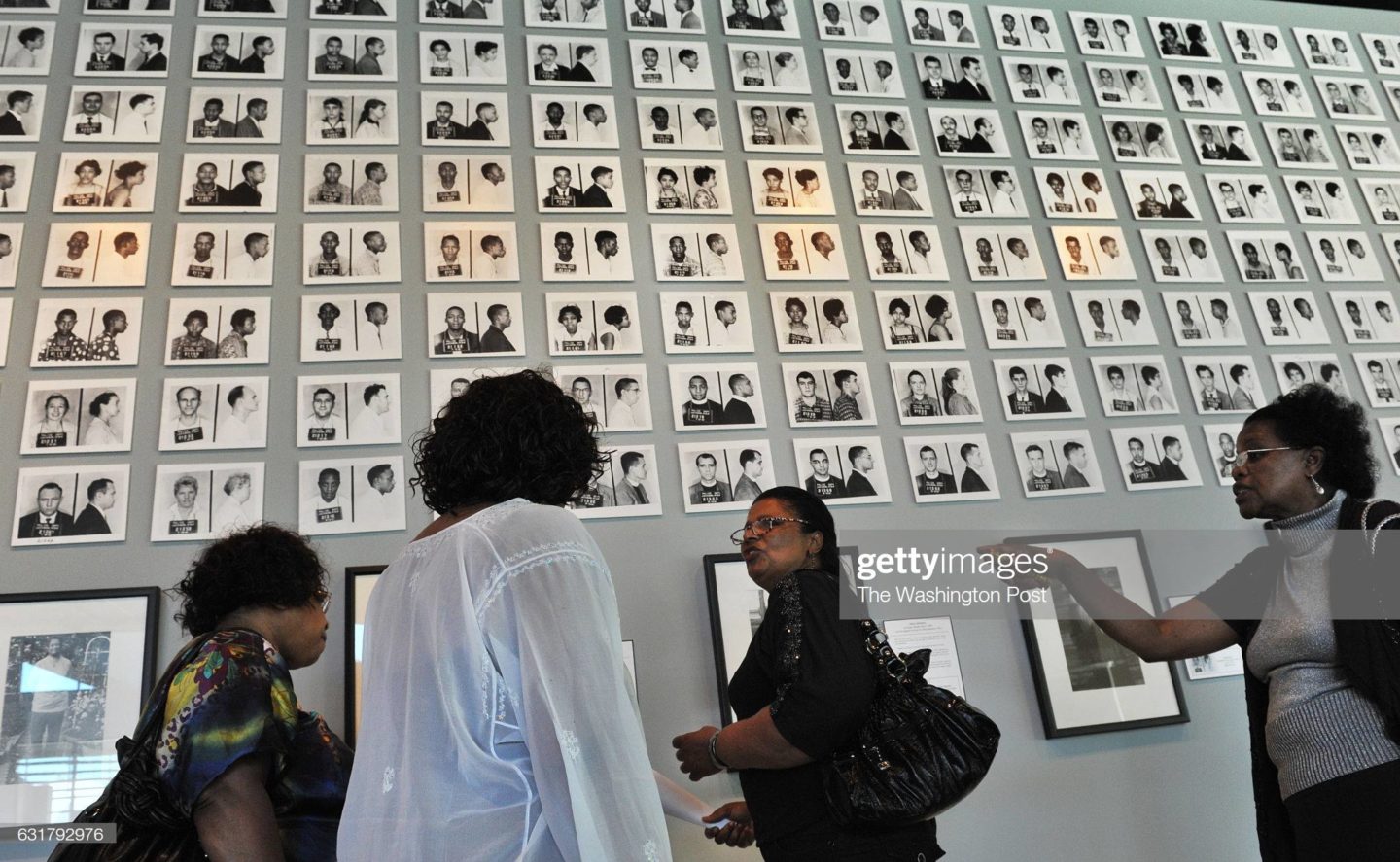

Unfortunately, the Freedom Riders never made it to New Orleans. The activists and their followers made with massive violence, both from racists and Ku-Klux-Klan supporters and from the US system of justice. Until the end of summer of 1961 more than 300 people who spontaneously joined the action were arrested pursuant to the state laws.

In April 2011, in the Mississippi Museum of Art an exhibition was open to commemorate the 50th anniversary of The Freedom Ride.