Anti-fascist Exhibition

Contemporary Art Society

The Contemporary Art Society was founded in Melbourne, in July 1938. The association whose founders included George Bell, Rupert Bunny and Adrian Lawlor was formed in response to the persistent rejection of modern art by the majority of the Australian art world’s establishment. In 1930s, the art community was predominated by members of the Academia who were conservative both in their views and in their approach to art. Most of them were closely associated with the political class. Their aversion towards modern art, and in particular to the output of European artists, was coupled with reluctance, commonly encountered in members of the elites, towards foreigners and refugees coming to Australia seeing a safe place from the nightmare of fascism and war, particularly the Jews.

Already in 1937, Robert Menzies (Prime Minister of Australia between 1939 -1941 and 1949-1966) publicly stated that:

“Great art speaks a language which every intelligent person can understand. The people who call themselves modernists today speak a different language.” http://melbourneblogger.blogspot.com/2011/09/anti-fascist-art-exhibition-melbourne.html [access on 22.08.2019].↩︎

Such an attitude was in tune with the antisemitism and xenophobia commonly found in the society at the time, as manifested by the demands to close the borders and by widespread disbelief in the scale of the war crimes committed in Europe by the Nazis. The Contemporary Art Society, which was criticized on many occasions for ”supporting the art of foreigners” was founded not only in order to bring together young radical artists practising new forms of art (including many immigrants and refugees) and oppose the cultural conservatism and promote modern art, but also to openly protest against the fascist ideology and aggressively nationalist anti-refugee rhetoric adopted by Australian politicians and cultural elites and to highlight the ideological connections between the two dangerous narrations. For CAS members, fascism was not an abstract issue, a political movement which does not exist locally or a demon taking its toll on the other side of the planet. They recognized the first germs of the same evil, a similarly barbarian way of thinking in their local environment among the members of the establishment referring contemptuously to the “Jewish founders of the so called modernism”.

In its original form, CAS survived until 1947 and during that time organized a series of politically engaged exhibitions, promoted young, modern artists, supported foreign artists who wanted to settle in Australia and carried out educational activities.

Anti-Fascist Exhibition

The Anti-Fascist Exhibition prepared by the Contemporary Art Society was opened on 8 December, 1942 in Atheneum Gallery in Melbourne (later on a slightly modified exhibition was also presented in Adelaide). The impressive show was a collective voice of young, emerging artists united in their artistic protest against the crimes of fascism. In the declaration included in the exhibition catalogue they wrote:

“It is a truism to say that the best weapons to employ against political and military fascism are political and military. But then fascism is not only a political movement, it is an “ideology,” and as such has its own official philosophy, psychology and art. Fascist art is a scullery maid in the fascist kitchen, a servile wench dutifully parrotting her masters’ inhuman views of race, blood and state; throwing overboard the last 80 years of artistic history because they would encumber the political idea.

It is our task to see that the results of generations of artistic labour are not thrown away in the interests of any political idea. Incorporate the idea if you will. In our own social order there are art movements founded on a belief in mass and individual liberty, with all that is implied in the economic and political sense. Such works may seem to contain little direct reference to fascism, but that does not matter. They leave that to the politician. What does matter is that they are incompatible with the fascist stomach, and as such are its natural enemies.” The Anti-Fascist Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Atheneum Gallery, Melbourne 1942.↩︎

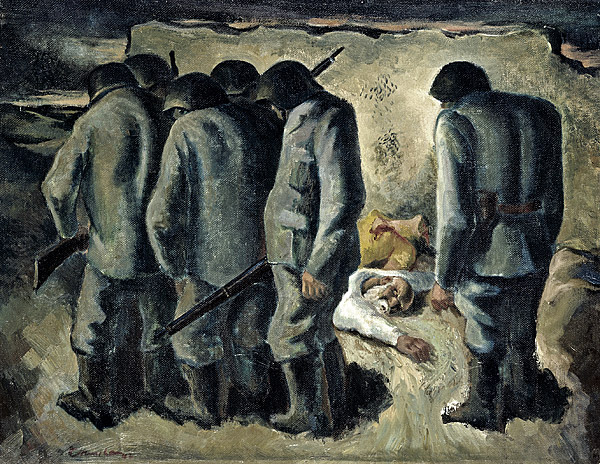

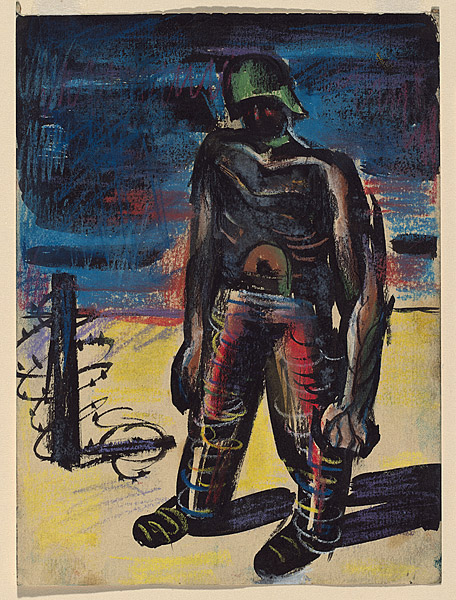

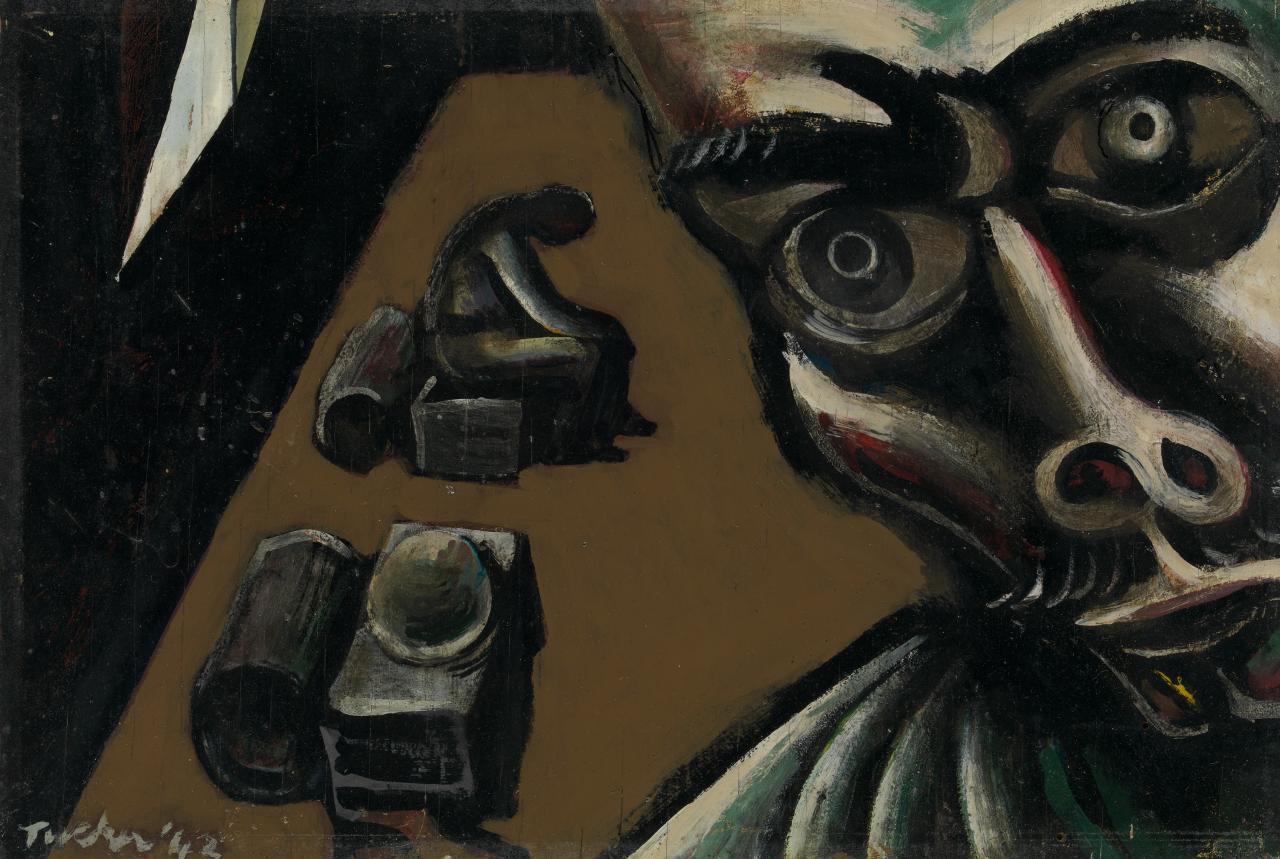

At the exhibition, anti-war and anti-fascist works were presented of numerous artists associated with the Contemporary Art Society, including John Perceval, Ailsy O’Connor, Sidney Nolan, Jacqueline Hick, Noel Counihan, Dorrit Black and James Wigley. Many of them referred directly to war times showing the atrocities, violence, despair, poverty and humiliation. Some touched upon the Nazi crimes in Europe. At the end of 1942, news about ghettos and concentration camps started to reach Australia but were in the majority of cases disbelieved. Apart from the works of local artists, the Anti-Fascist Exhibition was also an opportunity to present for the first time in Australia a wide selection of prints on paper by Käthe Kollwitz , a famous German anti-Nazi and anti-war sculptor and painter.

A member of the Contemporary Art Society who greatly contributed to the organization of the show was Yosl Bergner, a Jewish painter raised in Poland who in 1937 escaped from Warsaw where antisemitism was on the rise. The artist emigrated to Australia where he studied painting in the National Gallery School in Melbourne. His works displayed at the exhibition included both the ones stemming from his own memories from the capital of Poland, enhanced by press releases describing the situation in ghettos, antisemitic violence and the war horror and the scenes observed in Australia, in particular the poverty and social exclusion of Indigenous Australians. Comparing the two types of experience, Bergner pointed out the similarities between the oppression suffered by Aboriginal people in Australia and the tragic fate of Jews in Europe.