Artists’ International Association

Difficult beginnings for Artists’ International

The association was founded in 1933 in London under the name Artists’ International on the initiative of three British artists and communist sympathisers, painter Cliffe Rowe, illustrator, graphic artist and sculptor Pearl Binder and industrial designer Misha Black, who was the first to become president of the organisation. The first AI meetings were attended by a small group of young, socially and politically engaged artists and creators, including brothers Ronald and Percy Horton, Peggy Angus, Clive Branson, James Fitton, James Boswell, Betty Rea, Hans Feibusch and Edward Ardizonne and were held in Black’s place – a small, modest room with no electricity where boxes stolen from the market on Covent Garden served as seats A. Spawls, ‘Conservative in art, radical in politics’: James Boswell and the Artists’ International Association., „Apollo. The International Art. Magazine”, 25.05.2016, https://www.apollo-magazine.com/conservative-in-art-radical-in-politics-james-boswell-and-the-artists-international-association/ [accessed on 20.08.2019]↩︎.

Artists’ International came into being at a time when economic problems and, with them, social and political conflicts were rapidly increasing in the UK. The state’s economy was in dire straits, unemployment was rising rapidly and records were being broken, and the government was radically cutting benefits and limiting social policy. London was regularly paralysed by thousands of protesters taking part in so-called “hunger marches”, which were repeatedly brutally pacified by the police. The ubiquitous poverty, violence and growing feelings of frustration and disappointment in society fed the fascist movements, which were very successful in managing these moods. In 1932, Oswald Mosley, fascinated by Mussolini, founded the British Fascist Union – a political grouping of British fascists, Nazis and nationalists, which had about 50,000 members and an important part of which were aggressive, paramilitary militants. As Misha Black wrote ”we all had the feeling that the political situation was becoming intolerable” Ibidem.↩︎.

Members of the AI learned te hard way the effects of the economic crisis and of the unstable socio-political situation. Most of them did not come from rich families, had no savings and could not count on any financial support. After graduation, young artists and creators had problems finding their livelihoods and earned money doing various types of low-paid commercial jobs: they designed advertising posters, notices, leaflets or covers for books and magazines. They found it difficult to find strength and time to continue their artistic activity. They were not interested in the endless discussions on the superiority of cubism over surrealism that took place in the narrow, elite circles of the British art world. Artists’ International was created to unite young, radical, artists who sympathised with communists and who wanted to create art that was close to reality and the everyday problems of the British working class; art that was accessible and understandable to the masses; art that would fight for the rights of the poor and the unemployed; art that would unequivocally oppose both the anti-social policies of government and the growing fascist movements.

Initially, only about 30 people belonged to Artists’ International. The organisation was deeply involved politically and quite radical, working closely with the British Communist Party, to which some of its members belonged. In its founding declaration, the association was called the ‘ international unity of artists against Imperialist War on the Soviet Union, Fascism and Colonial oppression” L. Morris, The Artists’ International Association, ”Marxism today”, August 1983, p. 40.↩︎ , with the main aim of supporting and spreading Marxist thought through cultural and activist activities and cooperation with similar organisations from other countries, including groups of artists and communist sympathisers from Mexico, the USA, the Soviet Union and France. Artists affiliated with Artists’ International rejected the concept of ‘art for art’s sake’, they were not interested in modern forms, abstraction, surrealism or cubism – they postulated realistic, socially and politically engaged, readable, understandable and useful work. Instead of drawing beautiful paintings (some AI members, such as James Boswell, had abandoned their paintings in general), they preferred to draw illustrations and caricatures (e.g. for Left Review magazine); design propaganda posters and flyers; distribute mass-produced graphics; prepare flags and banners for demonstrations; collectively create large-format murals; and organize educational travelling exhibitions and shows of politically and socially engaged art, such as the exhibition “The Social Scene”, which Artists’ International organized in 1934 in London on Charlotte Street..

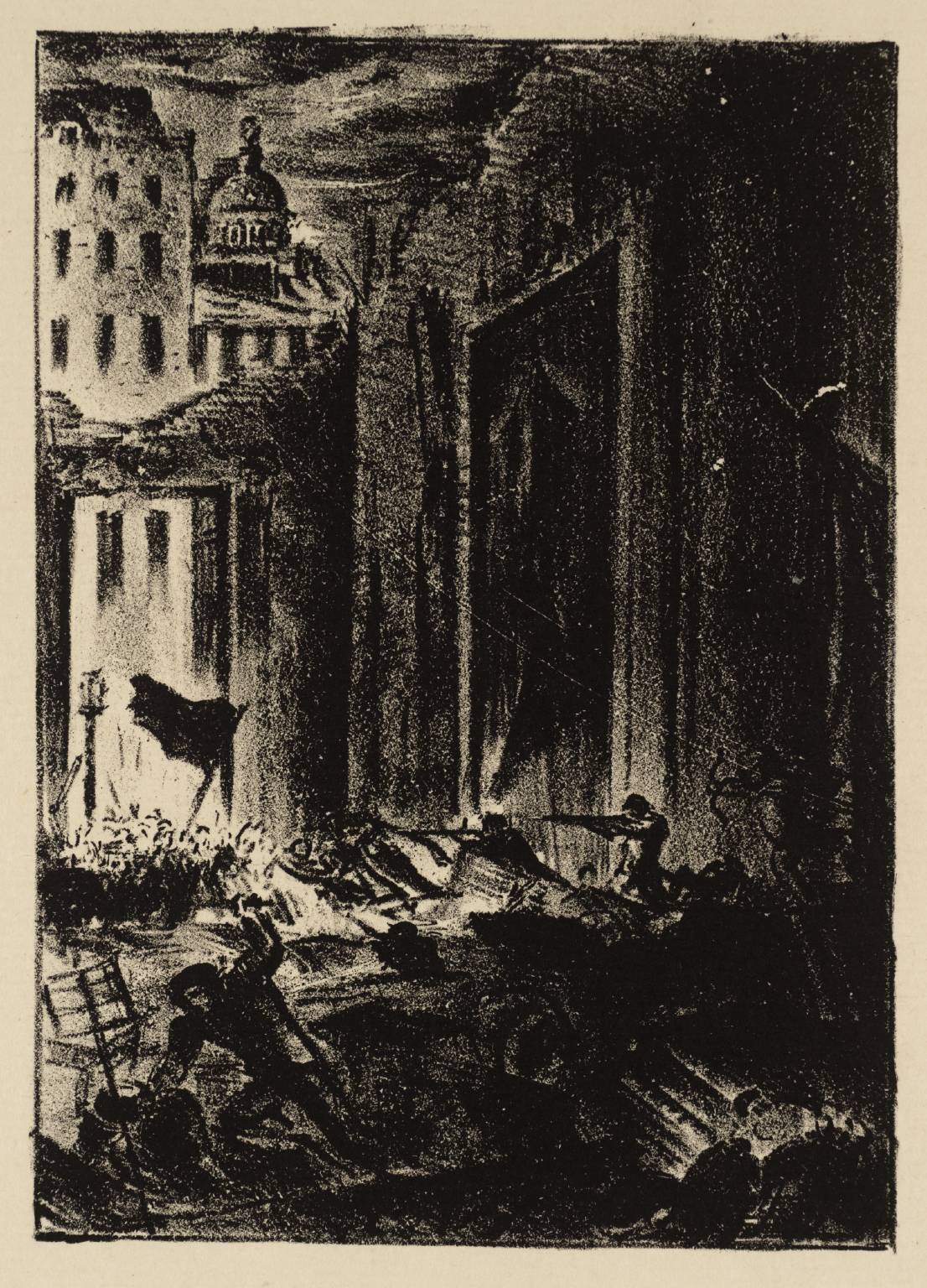

The Fall of London

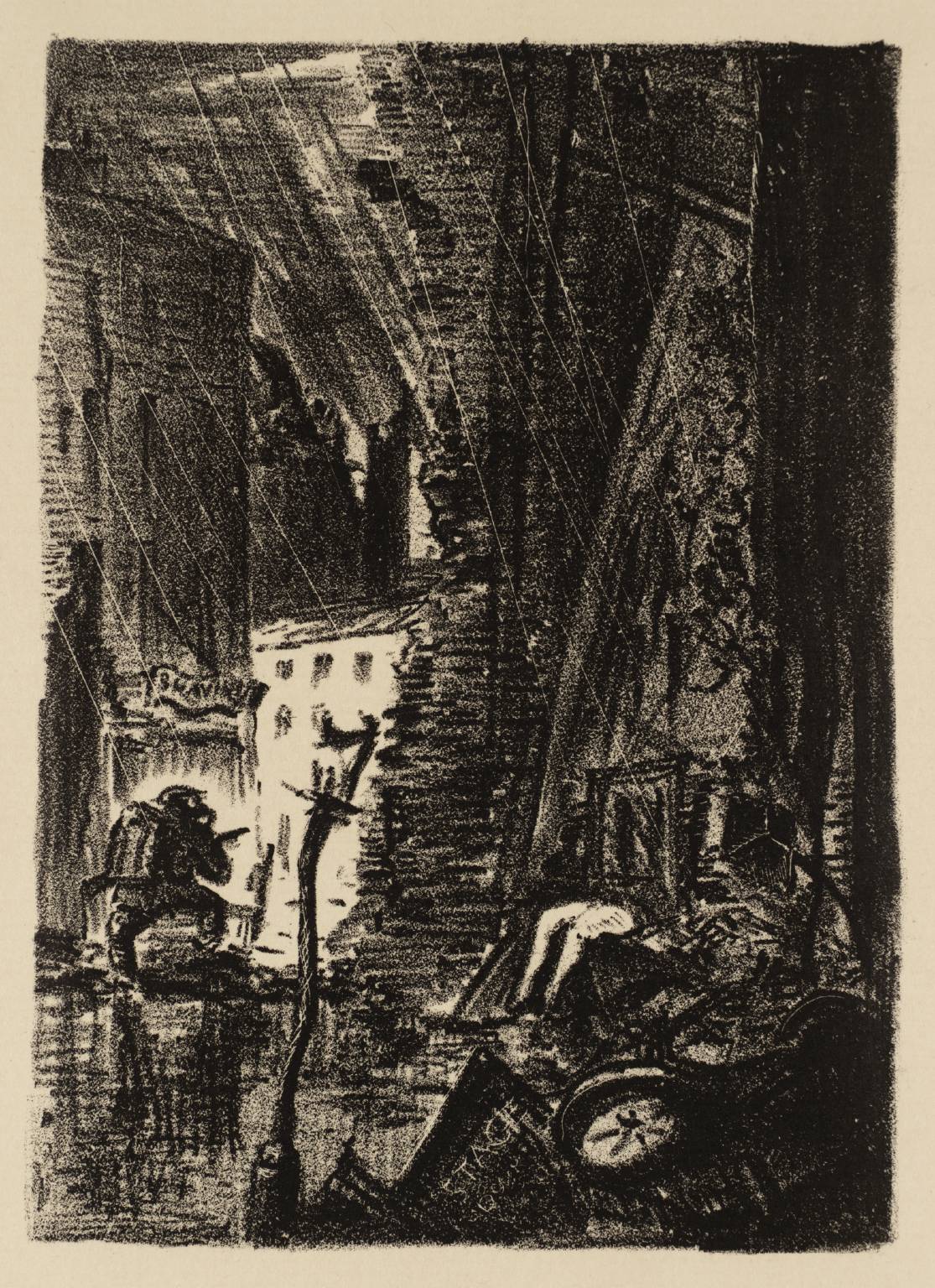

One of the most interesting examples of the early work of Artists’ International is the 1933 series of lithographs The Fall of London by James Boswell. Although they were not finally published in the 1930s (the general public only became acquainted with them many years after World War II, when they were found in the artist’s archives by his wife), they perfectly reflect the political climate of that period in Great Britain, illustrating social frustrations and anxieties and expressing the dark mood of waiting for the worst consequences of the growing popularity and power of Fascism.

Graphics from The Fall of London series depict the capital of Great Britain as a fallen city – instead of proud buildings, we see them as post-war ruins, ruins where Dantean scenes of chaotic, not revolutionary, not anarchistic fights take place. According to historian Ron Heisler, Boswell’s lithographs were originally intended to illustrate the 1934 science fiction book Invasion By Air by Frank McIlraitah and Roy Connolly https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/boswell-the-fall-of-london-the-colosseum-p11660, [accessed on 22.08.2019].↩︎, which tells the story of a fascist attack on Britain in the form of mass bombings using modern aviation. In their work, McIlraith and Connolly portray London during the invasion as a sea of ruins ruled by mass rebellion and anarchy. The constant clashes between the revolted people and the authorities and the army trying to control the situation turn into a bloody revolution, which can only be suppressed when the government uses British Nazi militia.

In Boswell’s dark lithographs, inspired by the famous anti-war graphic cycles of Jacques Callot, Francisco Goya or Otto Dix, it is easy to find references to the apocalyptic vision from the book – they depict destroyed iconic buildings in London; deserted squares; scenes of looting in deserted shops; frightened, scared residents hiding in the dark alleys of a destroyed city; numerous street fights and brutally suppressed demonstrations. The artist intended that his prints, used as illustrations of the popular novel, would reach the imagination of a wide audience, showing the British people the possible consequences of the economic and social crisis, the policies pursued by the British government and the further ignoring of the growing fascism. Perhaps McIlraith and Connolly did not expect that three years after the publication of Invasion By Air their prophecies would come true for the first time in the Spanish Guernica destroyed by fascist bombing. Similarly, James Boswell could not have known in the early 1930s that his paintings of destroyed London would become an everyday reality for the British capital during the Battle of Britain in 1940.

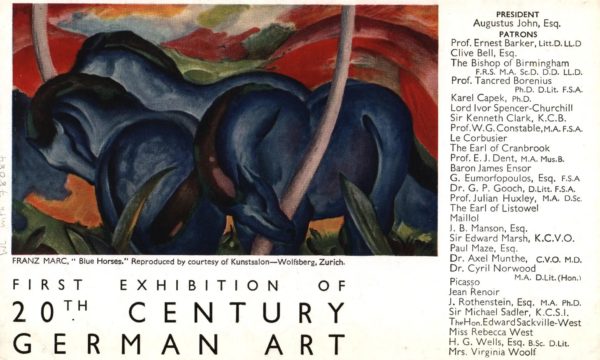

The People’s Front against Fascism and the reorganisation of the AIA

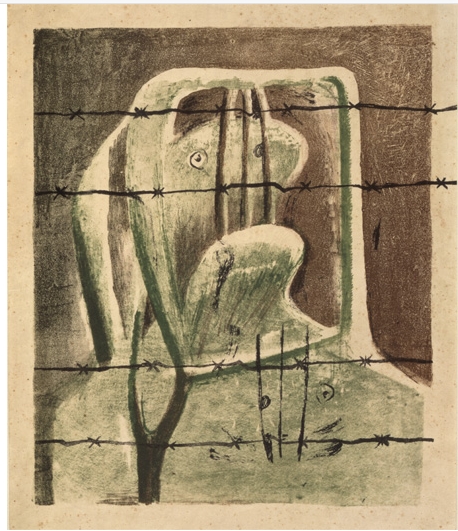

In 1935, after the announcement of the slogan “People’s Front against Fascism” at the 7th Congress of the Communist International, the members of Artists’ International decided to transform their organization according to the idea of a broad, anti-fascist alliance of communists, socialists, anarchists, liberals and other progressive forces. They changed the name of the association to “Artists’ International Association” and called the new structure “The United Front Against War and Fascism” L. Morris, op.cit.↩︎ and their aim was ” Unity of Artists for Peace, Democracy and Cultural Development” https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/artists-international-association, [accessed on 22.08.2019].↩︎. The direct references to Marxist thought and Communist Party and the recommendation to create only realistic art disappeared from the new statute of the organization. The re-established AIA has abandoned radicalism and its former doctrine in favour of building a broad anti-fascist coalition and opening up to various ways of expressing opposition to war and fascism. From 1935 onwards, t=active members of the organization were not only full-time cartoonists and satirists and supporters of useful art, subordinated to strictly political and realistic goals, but also artists experimenting with modern forms – expressionists, surrealists or abstractionists .

The reform of the AIA has contributed to a significant expansion of the membership base and increased interest in the association – in 1936 there were already over 600 people working there, including teachers, students, amateur artists, as well as numerous recognized artists such as Laura Knight and Henry Moore. AIA also collaborated with the British art world celebrities of the 1930s, such as the front painter Paul Nash, who showed his works at exhibitions organized by the association, or the critic and theoretician of modern art Herbert Read, who supported the organization’s activities and published his essay on revolutionary art in AIA’s 1935 publication entitled “The revolutionary art of the 1930s”. Read’s text, in which he puts forward the thesis that truly revolutionary and critical, as well as politically and socially engaged art, should not cling to realism, but should freely experiment with modern forms, was part of a heated debate constantly taking place within the organization. Although the members of the AIA agreed that their work had to implement the slogan “against war, against fascism” and reach out to a wide audience and mobilize the masses, it was difficult for them to agree on what means should be used for this purpose. There were both supporters of realism (as well as socialist realism), surrealists, expressionists, post-impressionists and representatives of the academy, and disputes between them were an integral part of the association’s activities. At the exhibitions organised by AIA, the works of the representatives of particular styles were hung in groups on separate walls or in separate rooms. The break-up within the association also led to bizarre situations, as was the case with the International Surrealism Exhibition in London in 1936, which was officially protested by the AIA, despite the fact that the works of a large group of members were presented there.

Despite the fact that the artists and creators associated in the Artists’ International Association were not united by a common style, the activities of the organization after 1935 were extremely resilient and effective. Members of the AIA published their own magazine and other publications, designed leaflets and posters, organized traveling art and educational exhibitions, created numerous illustrations and caricatures and cooperated with pacifist and feminist circles. They also tried to support artists fleeing fascism and Nazism to the UK, helping them to get the necessary visa documents and find a place to live and work. People associated with the AIA regularly took part in numerous anti-fascist marches and protests and politically engaged artistic actions, such as the First May parade in 1938, when a group of surrealists associated with the organization marched through London in the masks of the then British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain performing a Roman salute as a gesture of protest against the appeasement policy conducted by the British government in the 1930s, i.e. concessions to fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.

Spanish Civil War and AIA exhibitions

The new Artists’ International Association, reformed in 1935, organised at least once a year an exhibition devoted to social, political and anti-fascist issues, presenting works by its members and invited British and foreign artists. At the end of 1935, on the initiative of the AIA, a show entitled “Artists Against War and Fascism” took place in Soho Square in London. The show was attended by people associated with the organization as well as recognized British artists and a group of young, modern avant-garde artists, including Robert Medley, Barbara Hepworth, Paul Nash, Laura Knight and Henry Moore. The exhibition, which was clearly anti-fascist and sharp in its political expression, attracted more than 6000 visitors, and in the “Left Review” it was called “something between a demonstration and a national gallery” N. Copsey, A. Olechnowicz (red.), Varieties of Anti-Fascism: Britain in the Inter-War Period, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2010, p. 40.↩︎.

After the outbreak of civil war in Spain in 1936, members of the Artists’ International Association became extremely involved in organizing help for anti-fascists and anti-fascists fighting on the continent. The income from subsequent exhibitions of the association was used to support the republican forces of Spain – for example, with the money from the auction accompanying the “Artists Help Spain” show, a field kitchen was purchased and sent to the front G. Van Hensbergen, Guernica: The Biography of a Twentieth-Century Icon, Bloomsbury, New York 2004, p. 86-86.↩︎. Members of the organization collected funds by selling their artistic works (this way they managed to finance, among others, an ambulance donated to the Spanish army) and taking part in charitable events. They also actively supported the Artistic Refugee Committee or the General Fund for the Support of Children and Women Suffering in Spain.

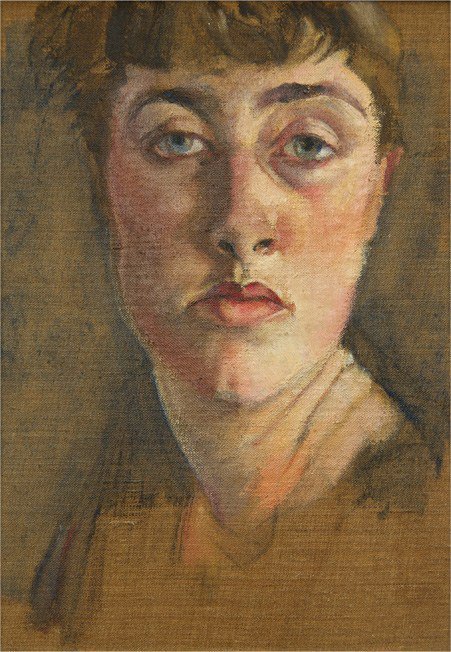

Part of the politically engaged artistic community in the UK decided to support the Spanish cause by going directly to the front and fighting in the ranks supporting the republican army of International Brigades, for which the artists of the AIA have made a huge flag. One of the most famous symbols of the involvement of the British and artistic circles in the Spanish Civil War was a female AIA member, painter and sculptor Felicia Browne, the first British volunteer to die during the conflict.

The Artists’ International Association also took part in the organisation of the Pablo Picasso’s Guernica show in Great Britain, which was visited by tens of thousands of people, during which money and gifts were also collected for Spanish anti-fascists. For instance, to see the painting in 1939 in the London Whitechapel Gallery one had to “pay” with a pair of leather shoes, which were then given to Republican soldiers. A few weeks later, “Art For the People” – the last pro-peace exhibition organised by the AIA before the outbreak of World War II – took place in the same institution and was seen by several hundred thousand viewers within a few weeks.

World War II and the end of anti-fascist involvement of Artists’ International Association

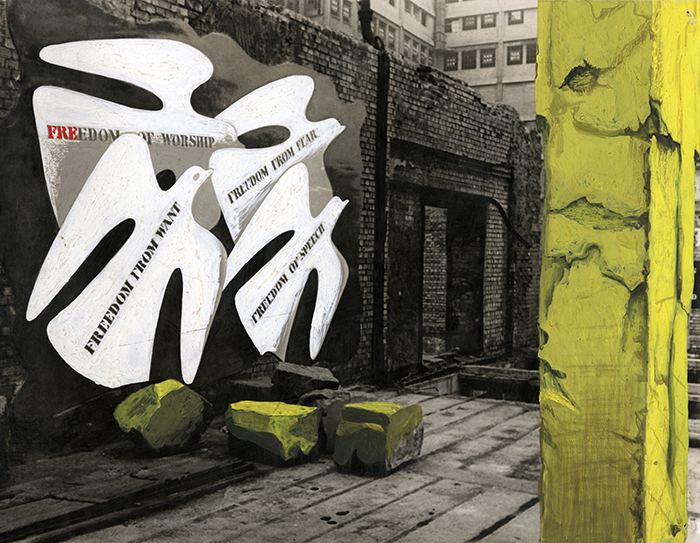

During World War II, most of the members of the AIA were involved in the production of propaganda material for the British government and army – they created widely-distributed pro-peace, anti-fascist posters and leaflets promoting resistance. This was the field of expertise of the organisation’s graphic designer of German origin, Henri Kay Henrion, who after the war became one of the fathers of what we call today “corporate identity”, understood as a coherent system of visual identification. Henrion also designed anti-war exhibitions organized by the AIA during the conflict, such as the famous “For Liberty” show, which took place in 1943 in the canteen room in the basement of the bombed John Lewis department store in London.

At the end of the war, the Artists’ International Association had over 1000 active members, but as the organization grew, it gradually gave up on activism and sharp, ideological message. In 1953, the declarations of anti-fascist attitudes and political involvement were removed from the AIA’s statutes, thus transforming them into an ordinary, apolitical exhibition association. The organization functioned in this form until 1971.