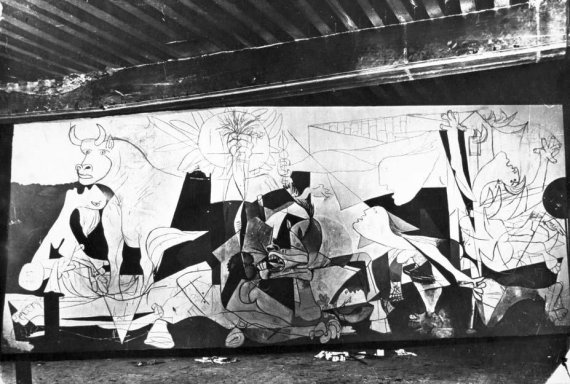

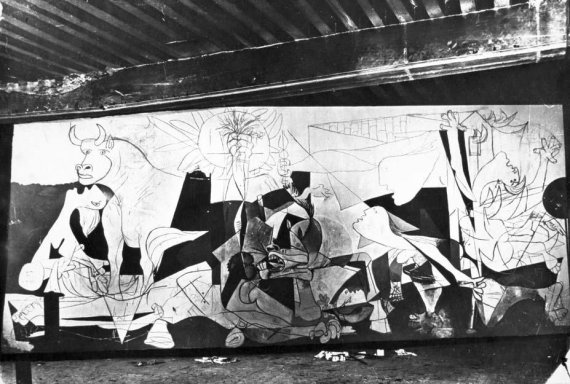

Pablo Picasso, Guernica

Fighting with paintings

The Spanish Civil War (Guerra Civil Española), which took place between 1936 and 1939, was a lost battle against fascism. Republicans loyal to their legitimate representatives, the left-wing Second Spanish Republic, in alliance with communists and anarchists, fought against the nationalist revolt, an alliance of phalangists, monarchists, conservatives and Catholics led by a rebellious military group, including General Francisco Franco. Nationalist forces received support from Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, while the republican side was supported by the Soviet Union and Mexico. Other countries, such as the United Kingdom, France and the United States, while recognizing the Republican government, nevertheless followed an officially adopted policy of non-intervention. Despite that, tens of thousands of citizens from neutral countries were directly involved in the conflict. They fought mainly in pro-Republican International Brigades, which received volunteers and fugitives from nationalist regimes. One of such international units was the 13th Józef Dąbrowski Brigade, voluntary military units formed mainly by Poles, as well as other persons with the Polish citizenship fighting on the republican side . Due to the situation in international politics at the time, the war in Spain was waged on many levels: it was a class struggle, a religious struggle, a battle between dictatorship and republican democracy, between revolution and counter-revolution, between fascism and communism. The Spanish civil war was believed to be a general rehearsal before World War II. Nationalists defeated the Republican army in early 1939; as a result, they ruled Spain until Franco died in 1975.

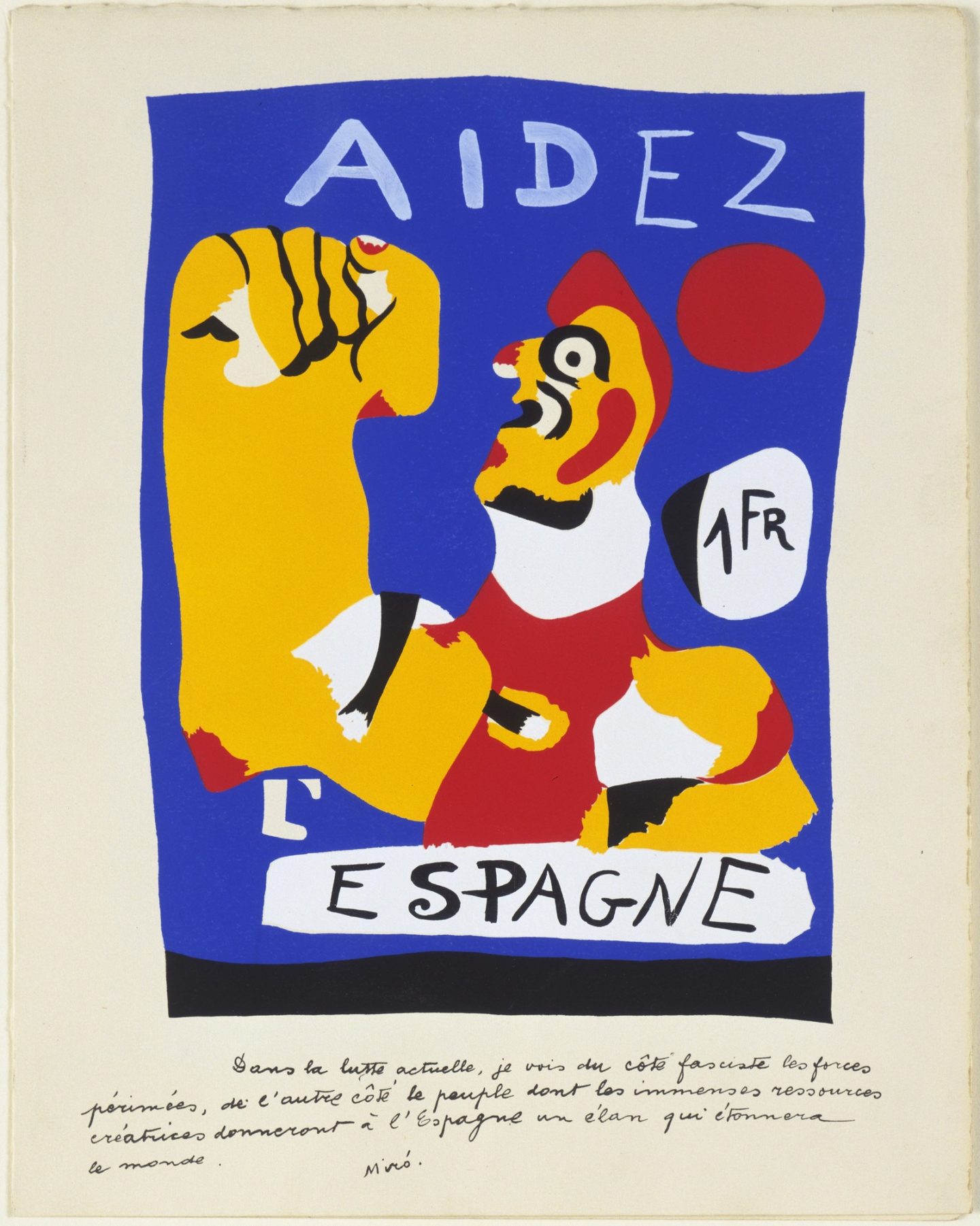

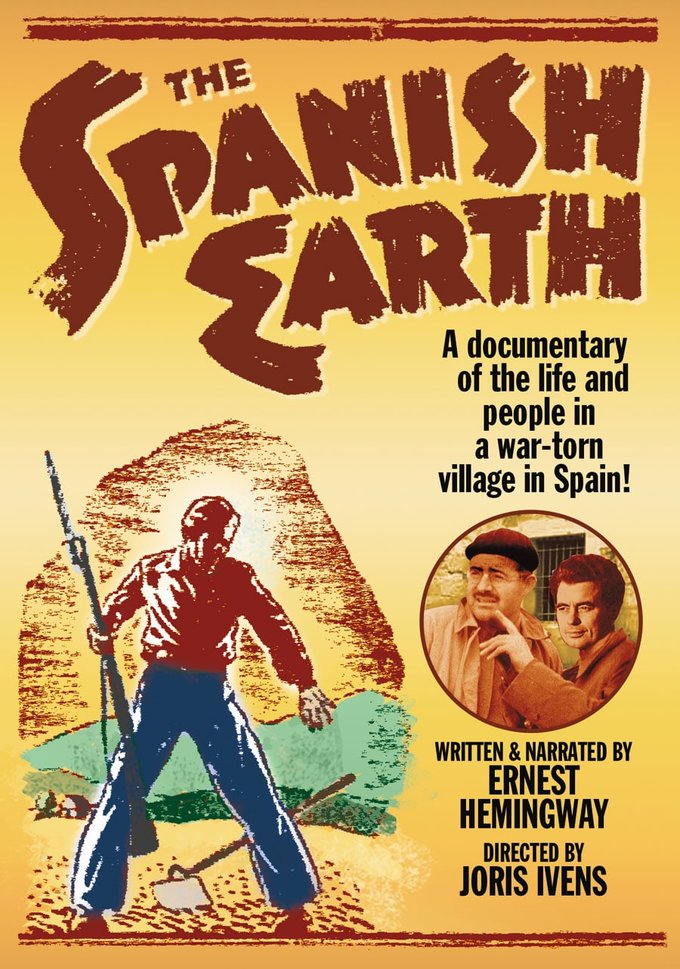

During the civil war, people all over the world received information about the situation in Spain and the effects of the fighting not only through the media, but also through the propaganda art and artistic statements of individual artists. All forms and ways of communication – films, posters, books, radio programmes and leaflets – had a huge impact on public opinion in Europe and the USA. The propaganda fight with paintings, carried out on a large scale by both nationalists and Republicans, allowed the Spanish to spread the news about the civil war all over the world. Films co-produced by well-known early 20th century writers such as Ernest Hemingway and Lillian Hellman were used as a way of publicising Spain’s need for military and financial aid: for example, The Spanish Earth, which premiered in the USA in July 1937, reported on the situation in Madrid under siege by fascists. In 1938 George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia was published in Great Britain – a personal description of his experiences and observations from the war. In 1939. Jean-Paul Sartre published in France a short story titled The Wall (Le Mur), in which he described the last night of prisoners sentenced to death by shooting. In July 1937 an exhibition of posters from the Spanish Civil War was held in New York City, prepared by the North American Committee for the Assistance of Spanish Democracy and the Office for the Medical Assistance of Spanish Democracy.

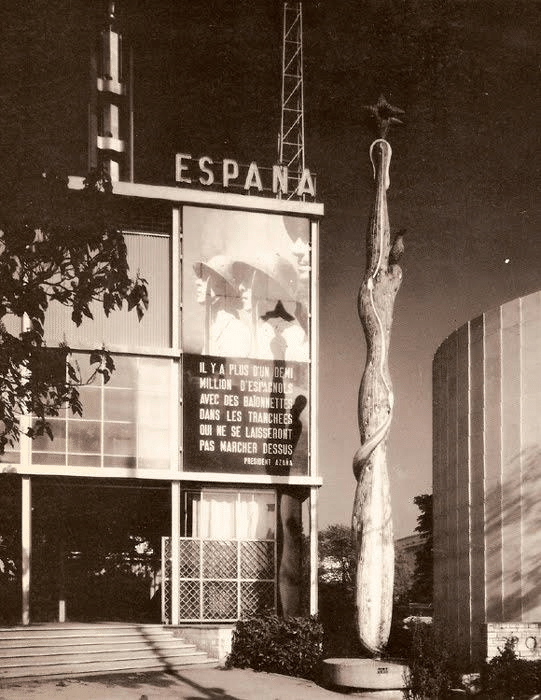

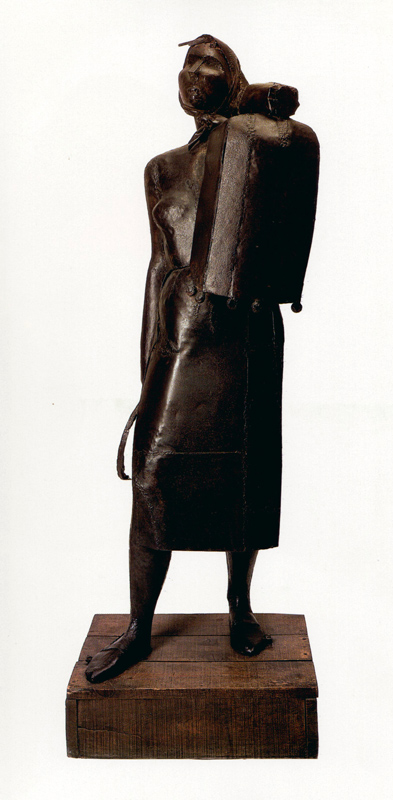

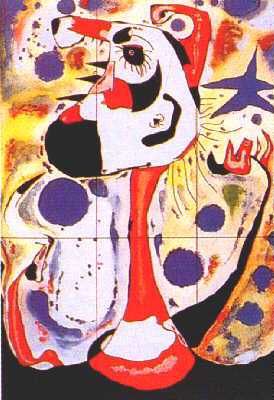

Apart from propaganda posters, films and texts, other works of art were also created which were involved in the political situation – frequently anti-war, focused on the suffering of civilians. These were often modern, huge sculptures and paintings. Suffice it to mention here the sculpture by Albert Sánchez Pérez called The Spanish People Have a Path that Leads to a Star (El pueblo español tiene un camino que conduce a una estrella), a 12-metre high plaster monolith, representing the struggle for the socialist utopia or La Montserrat by Julio González, an anti-war sculpture, which took its title from a mountain near Barcelona, built of hammered and welded sheet iron, depicting a peasant mother who carries a small child on one hand and holds a sickle in the other. Other famous works of art created as a reaction to the Spanish Civil War include Alexander Calder’s Mercury Fountain (Fuente de Mercurio) and The Reaper (El Segador) painted by Joan Miró, also known as the Catalan Peasant in Revolt (El campesino catalán en rebeldía). It depicts a peasant waving a sickle in the air. As the artist himself said about his work

”The sickle is not a communist symbol. It is the reaper’s symbol, the tool of his work, and, when his freedom is threatened, his weapon” B. Meritxell, A hymn of freedom, https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-22-summer-2011/hymn-freedom↩︎.

Bombardowanie Guerniki, jako akt przemocy wymierzonej w ludność cywilną zszokowało i zainspirowało do działania wielu artystów, w tym autorów kompozycji muzycznych oraz poetyckich. W reakcji na atak powstały m.in. jeden z pierwszych utworów elektroakustycznych Patricka Ascione, kompozycje muzyczne Octavio Vazqueza (Guernica Piano Trio) oraz wiersze Paula Eluarda, m.in. Zwycięstwo Guerniki (La victoire de Guernica). O Guernice opowiadają również liczne formy rzeźbiarskie, malarskie i filmowe: rzeźby René Iché, obraz autorstwa Rene Magritte’a o tytule Czarna Flaga (Le Drapeau Noir) oraz najsłynniejsze dzieło spośród nich – mural Pabla Picassa, Guernica.

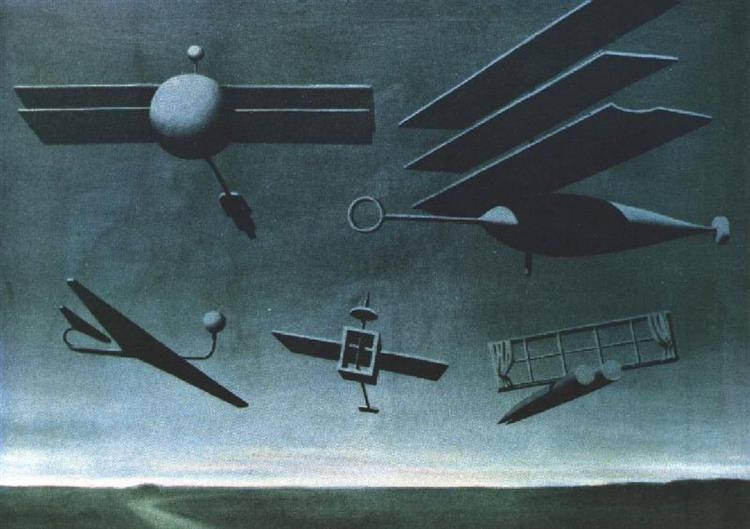

The bombing of Guernica as an act of violence against civilians shocked and inspired many artists, including authors of musical and poetic compositions. The works of art created in response to the attack included some of Patrick Ascione’s first electroacoustic pieces, Octavio Vazquez’s music compositions (Guernica Piano Trio) and Paul Eluard’s poems, such as the Victory of Guernica (La victoire de Guernica). Guernica is also the subject of numerous sculptural, painting and film forms, such as the sculptures by René Iché, a painting by Rene Magritte entitled the Black Flag (Le Drapeau Noir) and the most famous work on the subject – the Guernica mural by Pablo Picasso.

Death as the illumination of life

Guernica was created over five weeks between May and June 1937. The work commemorates the events of April 26, 1937, when the ancient city of Guernica in the north of Spain considered to be the oldest capital of the Basque culture, was bombed . The air raid was carried out by Nazi Lufftwaffe troops, supported by planes of Italian fascists. The action was a military experiment, during which the strength of the newly developed explosives was tested. The attack was accompanied by a media and propaganda campaign prepared in advance the goal of which was to to blame the destruction of the city on the Basque communists. The aim of the bombardment was primarily to undermine the moral values of citizens opposed to Franco’s coup.

The attack aroused controversy and triggered international protests, because the military air force attacked civilians – to this day the bombing called Operation Rügen (Operation Reprimand) is considered to have been a war crime against humanity. The number of victims has never been precisely determined; the Basque government reported 1,654 people killed during this time, but this figure probably does not include those who died from wounds and bodies found under the rubble.

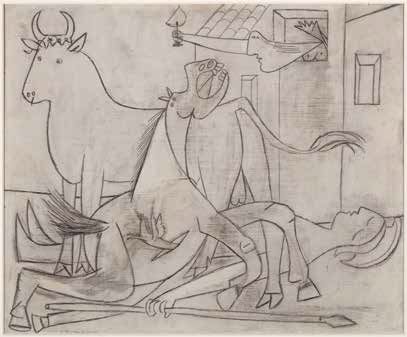

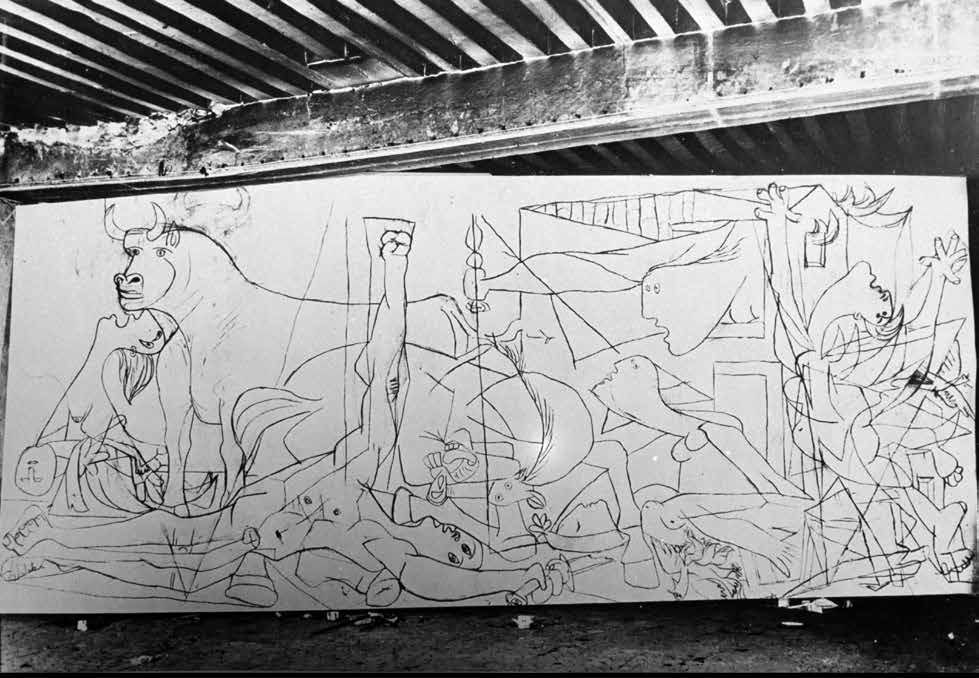

Picasso made preparatory sketches for the mural a few days after the attack, 10 days later he worked on the canvas. The mural was ready in early June – in just over a month Picasso finished his great work. We know the process of creating Guernica thanks to the photographic documentation kept by Picasso’s partner, Dora Maar. Dora Maar has been taking pictures of the first attempts and sketches since the beginning of May 1937. Picasso prepared many sketches for the mural, but even the first ones already contain specific elements that can be found in the finished mural: a bull, a horse, a woman with a lamp and a mother with a dead child in her arms. The artist also quickly decided on a dark, monochromatic palette, which dominates the work. Single light sources, a bulb and a lamp in the hand of one of the women are shining against the background of the black sky.

In the next stage of the work, an outstretched hand appears in the centre of the canvas, holding the ears against the background of the sun – a communist worker symbol, later changed by Picasso into an eye filled with a light bulb. The human hand and the human cause disappeared. The light of a light bulb throws geometric patterns on the picture, divides and cuts the picture – it is abstract and mechanical. Picasso worked in a collage way, pinning to the composition elements of wallpapers and newspapers that marked specific shapes. This moment was also captured by Dora Maar in her photographic documentation.

Guernica is filled with chaos, fire, despair and death – in the picture we see a woman jumping out of a burning building, faces twisted with suffering, lips opened in a silent scream. The central part of the composition presents a mixture of human and animal limbs. Picasso replaces the monstrosity of war with the image of its victims – the bodies of women and animals twisted and joined in pain. As emphasized by an expert on Picasso’s work, art historian T.J. Clark, women in Picasso’s art are always “machines for suffering” (”machines à souffrir”) and here they have to suffer too T.J. Clark, Picasso and Truth. From Cubism to Guernica, Princeton University Press, Washington 2013, p. 262.↩︎. The particular story of the bombing of Guernica gets universalized. Picasso does not point hi finger at the guilty, but rather indicates the senselessness of human suffering during the war. The agony of the city is viewed by the symbol of Spain – a bull. Guernica is the very essence of political events of that time, but also Picasso’s response to fascism and communism and the modern ways of conducting war. As T.J. Clark emphasizes, such a large canvas had to be composed in parts:

”In the case of Guernica, it is obvious that the group in the centre dominates, and the agonies on both sides, while the woman falling out of a burning building, and the mother screaming under the head of a bull are subordinated to her […] This left and right side are, one might say, the wings of an altar” 3 T.J. Clark, Picasso i prawda. Mural, translated by K. Mazur [in:] Nigdy więcej. Sztuka przeciw wojnie i faszyzmowi w XX i XXI wieku (edited by J. Mytkowska, K. Szotkowska-Beylin), Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Warsaw 2019, p. 37-38.↩︎.

Guernica is a thoughtful and planned composition, showing a senseless death that should not end human life. It is an obscene death that occurs beyond time and for which no one was prepared.

The whole scene is lit by a light bulb symbolizing the agony of faith in science and progress. Probably the inspiration for the presence of light in the painting was a painting by Francisco Goya called The Third of May, 1808 (El tres de mayo 1808 en Madrid), which Picasso mentioned in 1937, shortly before he sent Guernica to the Paris World Exhibition in the Spanish Pavilion:

”And then, there is the enormous lantern on the ground, in the center. That lantern, what does it illuminate? The fellow with upraised arms, the martyr. You look carefully: its light falls only on him. The lantern is Death. Why? We don’t know. Nor did Goya. But Goya, he knew it had to be like that” André Malraux, Głowa z obsydianu, translated by A. Tatarkiewicz, [in:] Nigdy Więcej…, op.cit., p. 39.↩︎.

In Picasso’s paintings, death is enchanted in objects. In Guernica it is present everywhere and nowhere. It manifests itself as light, the illumination of life. Guernica is a response to death, violence and fascism, contained in the composition of the painting itself.

The largest, also in terms of size, Picasso’s canvas (3.5 m by 7.8 m) was first presented in July 1937 at the World Exhibition in Paris, in the hall of the Spanish Pavilion. The huge format of the work also carries symbolic and historical significance. As Francis Frascina emphasizes in his essay on the symbolism of Guernica:

”The size, scale and format of Picasso’s Guernica are reminiscent of ancient historical paintings dedicated to religious, mythological or historical events. As in that tradition, Picasso’s work is based on codes, symbols and allegorical attitude to the event indicated in its title. It is not a “real allegory” as in the case of Courbet’s Atelier painting from 1855. However, Picasso wanted it to have some propaganda function” F.Frascina, Picasso, surrealizm i polityka w 1937 roku, translated by J. Popowski [in:] Nigdy Więcej…, op.cit., p. 76.↩︎.

The canvas was too big for the space of the pavilion, but Picasso forced the designers to change the architectural plan. Next to the mural was Alexander Calder’s Mercury Fountain, another attempt to confront the horrible senselessness of death during the war – mercury, which was at that time Spain’s main export material, was flowing into the fountain through narrow water channels. Next, in the inner courtyard, Luis Buñuel prepared a projection space where films depicting civil war were shown. The entire pavilion was designed as a testimony to the atrocity of the war, which was to help raise funds to support the starving republican army.

Private and universal suffering

During the preparation and show of Guernica, the political moods in artistic circles were also hot and strongly divided. Not all artists supported the Republican government, especially after the Communist Party in Barcelona attacked the independent Marxist party and anarchist trade unions. Stalinist units also took part in the attacks. Many of Picasso’s friends, although at that time they called themselves communists, were anti-Stalinist. All of these heated political disputes and troubles are visible in successive versions of the mural and in the process of the creation of Guernica.

In this atmosphere of war, disputes and tensions Guernica was coolly welcomed by Parisian critics. Edouard Pignon, son of a miner and member of a Communist Trade Union write about the mural: ”As for the working class, in fact, it never saw it”. Others, like Paul Nizan, a close friend of Jean-Paul Sartre argued that Picasso’s art was both ”ivory tower” and ”effete” and suggested that “all attempts to bourgeoisify the workers with the art of their masters would fail” G. van Hensbergen, Guernica: The Biography of a Twentieth-Century Icon, Bloomsbury Publishing, Nowy Jork 2003, p. 72.↩︎.

However, Guernica’s subsequent travels, associated with the need to raise money to help starving Spain, including the shows in Oslo, Copenhagen, Manchester and New York funded by workers’ unions, were visited by thousands of viewers and spectators, proving the strength of the universal message of the mural. In his essay entitled The Success and Failure of Picasso, John Berger suggested that the strength of Guernica comes not only from the deeply personal mood of the work but also from the denial of history, understood as concrete material conditions or political struggles:

“Guernica […]is a profoundly subjective work – and it is from this that its power derives. Picasso did not try to imagine the actual event. There is no town, no aeroplanes, no explosion, no reference to the time of day, the year, the century, or the part of Spain where it happened. There are no enemies to accuse. There is no heroism. And yet the work is a protest – and one would know this even if one knew nothing of its history” J. Berger, The Success and Failure of Picasso, translated by J. Popowski [in:] Nigdy Więcej…, op.cit., p. 92.↩︎.

During the exhibition in Munich in 1955, Carl George Heise wrote in Die Zeit:

”What other aesthetist or intellectual could create a work as deeply moving as Guernica, which uses all imaginative means to move people’s hearts, so that as a result, all the anti-war manifestos of the world fade in comparison with it? Every day at the exhibition we see how even the mockers are silent in the dense crowd of viewers, standing up and holding their breath in front of this huge canvas” C.G. Heise, Picasso und kein Ende, translated by J. Popowski [in:] Nigdy Więcej…, op.cit., p. 94.↩︎.

Guernica is not only an artistic statement, but also a civil, civic statement – a protest of a helpless witness to the tragedy of his or her nation. The story of the end, death, destruction is treated in Guernica as a parable – the agony of the city, played out by mythical monsters and heroes. It is a suffering elevated to the rank of a public event, a social experience. This is how Picasso himself commented on the context of the creation of Guernica:

”What do you think an artist is? An imbecile who has only eyes if he is a painter, or ears if he is a musician, or a lyre in every chamber of his heart if he is a poet, or even, if he is a boxer, just his muscles? Far, far from it: at the same time, he is also a political being, constantly aware of the heart-breaking, passionate, or delightful things that happen in the world, shaping himself completely in their image. How could it be possible to feel no interest in other people, and with a cool indifference to detach yourself from the very life which they bring to you so abundantly? No, painting is not done to decorate apartments. It is an instrument of war for attack and defense against the enemy” P. Picasso, a letter from 1945 [in:] J. Sabartés, Picasso, Harry N. Abrams, New York 1955, p. 505.↩︎.

Guernica as a symbolic image of fascist violence has become a travelling work – physically and symbolically. It has made many journeys through the cities of the world, testifying to the horrors of war, but also serving as a symbol intercepted by successive generations who pour their own content into the picture, protesting against successive wars and conflicts of the 20th and 21st centuries.