Laboratory of Modern Techniques in Art

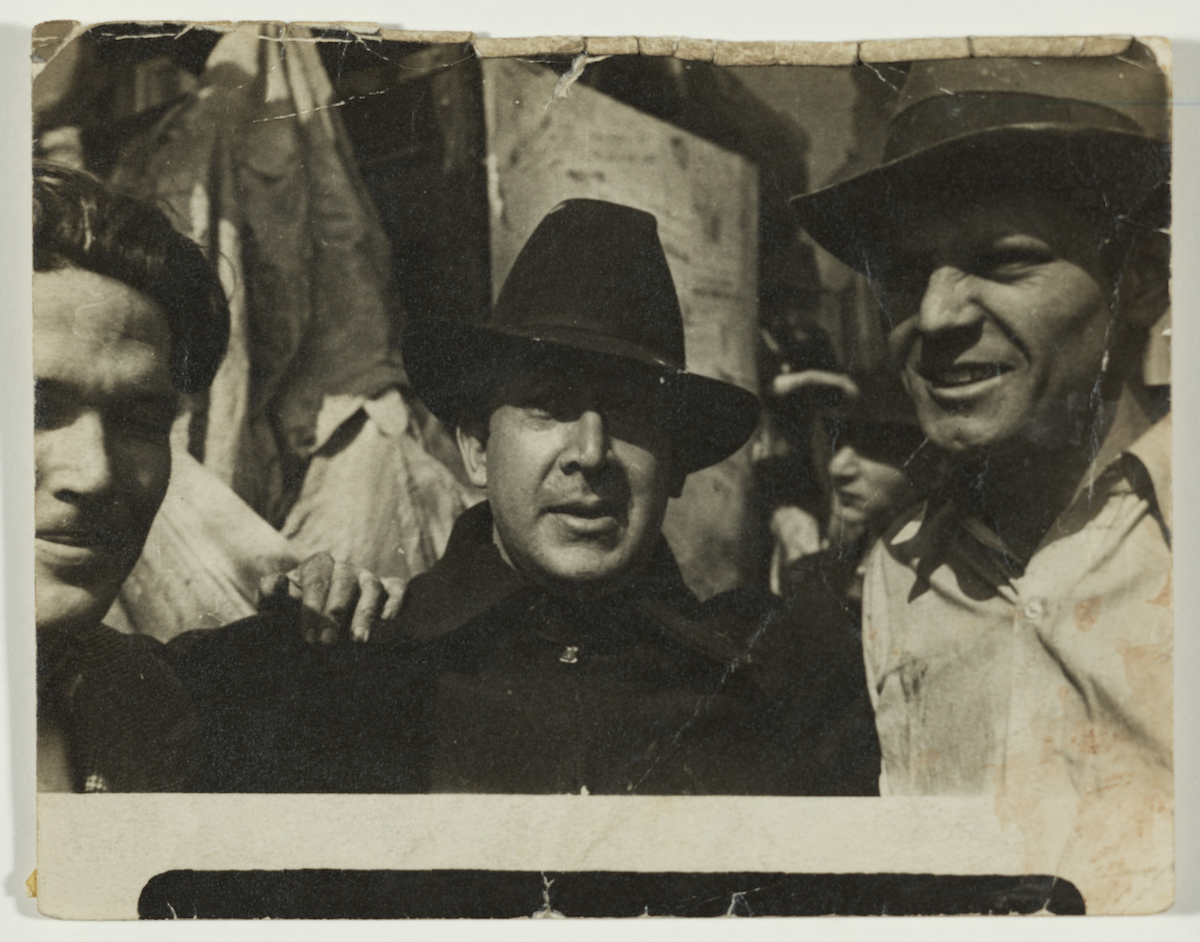

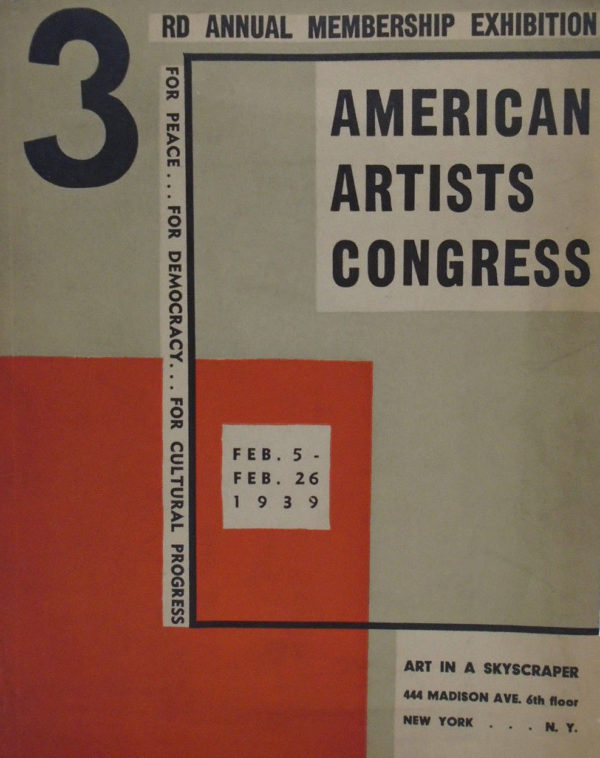

David Alfaro Siqeuiros was one of the members of a delegation from Mexico at the first American Artists Congress in February 1936 in New York. During the meeting he gave a fiery speech entitled The Mexican Experience, in which he presented the history of both the Mexican Revolution and the activities of Mexican muralists resulting, in his opinion, from political changes. Siqueiros was convinced that modern, progressive art always resulted from and followed emancipatory social movements. In his opinion, the development of creativity was only possible when artists joined forces with activists and, using the latest available techniques, produced works that were understandable and accessible to the general public, with a clear political message. In the summary of his stance, the Mexican painter spoke out explicitly not only against war and fascism but also in support of revolution – both in the society and in art.

Members of the AAC were very impressed by Siqueiros’ speech. Thanks to their support, as early as in March 1936, the Mexican artist managed to rent a studio near Union Square in New York, where his experimental collective art workshop began.

New York Manifesto

Shortly after the start of his venture called Laboratory of Modern Techniques in Art, Siqueiros published his Manifiesto de New York (New York Manifesto), a collection of ideas and principles guiding his venture. The methodology of work in the Laboratory was to be based on six pillars:

- Experimentation

- Research of technical aspects of art

- Studying the relationship between classical and modern techniques of art creation and the corresponding epochs

- Development of new art production techniques appropriate to modern times

- Producing public forms of works of art that are understandable and accessible to the general public

- Working and studying collectively in an environment without hierarchy

The main principle of the Laboratory was to experiment. Siqueiros believed that his contemporary art was stuck in an impasse – he wanted to produce monumental, public works that reached the masses and aroused political awareness among viewers, but were still technically archaic, using methods unsuitable for the era. The study of classical and modern artistic techniques and constant attempts to change, improve and mix them were to help create new working methods suitable for the times. Siqueiros in the Manifesto indicates concrete ways of creating works that, in his opinion, can be considered as modern within the different fields: he postulated the use of industrial paints and varnishes, metals, plastics, chemical processing, tools such as presses, airbrush or spray guns, photographs, film projections and all kinds of image reproduction methods. As he wrote in his Manifesto:

“This workshop intends to be experimental in purpose…. We intend to experiment with new theories of composition in the plastic arts…[and] we intend to experiment with modern methods of working collectively. […] Through a profound analysis of the relation of traditional techniques to their time, we intend to find the technique of our time;—for we consider also that so-called modern techniques are in reality archaic and consequently anachronistic.” E. Schlemovitz, David Alfaro Siqueiros’s Pivotal Endeavor: Realizing the “Manifiesto de New York” in the Siqueiros Experimental Workshop of 1936, CUNY Hunter College, 2016, p.30.↩︎

Siqueiros, however, did not focus only on formal explorations. It was equally important to him that modern art be public, based on the political commitment of the artist and a clear, emancipatory message to reach a wide audience, including, in particular, the working classes.

“Our problem is not only one of a physical and technical nature, but also to find forms of the widest possible public scope. In short, art for the people not art for the elite.” Ibidem, p. 31.↩︎.

Of key importance to the Laboratory’s activity was also the collective dimension of the work of the engaged individuals. Siqueiros did not consider himself a group leader, but a “technical director” or “practical guide”, and called his colleagues and associates “art laborers”. The Mexican painter unequivocally rejected the concept of the studio as a place of solitude, where the artist, isolated from reality, creates a memorable work. Instead, he proposed the idea of a laboratory or workshop, all members of which would have an equal status, carry out research together, create together, use common materials and knowledge, and b were jointly responsible, also financially, for the project itself. The people operating in the Laboratory did not have to be professional artists and artists – the willingness to learn and involvement in the proposed theoretical and practical programme was enough. Eventually, an interdisciplinary group worked in the Laboratory, consisting of painters, sculptors, photographers, architects and even chemists, each of whom could carry out their own individual projects as part of the collective’s activities.

Paintings

The Siqueiros’ Manifesto managed to attract a large group of young artists to the workshop, for many of whom it was one of the first steps in developing their practice. These included Jackson Pollock, Sande McCoy, George Cox, Louis Ferstadt, Axel Horn, Harold Lehman, Clara Mahl, Luis Arenal, Roberto Berdecio, Jésus Bracho and Antonio Gutíerrez. Although the Laboratory has only been in existence for less than a year, its anti-fascist, anti-war and pro-revolutionary activity has received a wide echo in the art world, and even beyond.

Today, the workshop is most often associated with a number of paintings by David Alfaro Siqueiros himself painted on boards. Despite the efforts of the creators, the Laboratory did not receive any orders for murals placed in public space, which, according to the Mexican artist, were the best opportunity to implement the ideas contained in the Manifesto. Therefore, the members of the workshop devoted themselves to painting monumental compositions on huge wooden panels. They were created using the “controlled coincidence” method developed by Siqueiros – the first, completely abstract layer of the works was created collectively using randomly selected tools, industrial paints, nitrocellulose varnishes, etc. Colours were splashed over the entire surface of the painting, often with the help of fancy constructions and cranes (which may have inspired Jackson Pollock to develop later his famous dripping method).

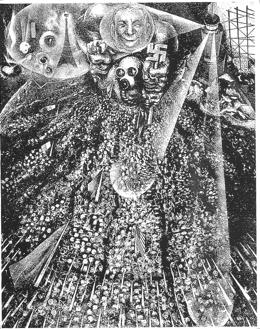

Despite his declared belief in experimentation, collective and non-hierarchical relations between art workers, it was Siqueiros himself who gave the final shape and expression to the work created in the Laboratory. The Mexican, faithful to the ideas of public and mass art, transformed his collaborative, declarative anti-war and anti-fascist abstractions into a more figurative, narrative and clear message. This is exactly how he created paintings such as The Birth of Fascism and No More! Stop the War! Siqueiros deeply believed in the idea of a united front against war and fascism and was actively involved in the American Artists’ Congress, where he presented works created in the workshop (although under his own name), so despite the conviction of the need for experimentation, the artist still put the communicativeness and clarity of his works in the first place.

In his later works, considered to be the greatest achievements of the Mexican artist of that period (in fact, at least partially created collectively by the Laboratory team), such as Collective Suicide and Cosmos and Disaster, there are fewer and fewer figurative additions and legible narratives, and more and more dark, apocalyptic abstract elements. These were created at the end of the workshop and were a direct reaction of the group to the dramatic news from Spain, where a brutal civil war broke out.

Functional Revolutionary Art

Apart from experimenting with painting or sculpting forms, the artists working in the Laboratory also produced much more “useful” works of art – posters, flags, banners and platforms used during demonstrations and political manifestations. As a member and chronicler of the group, Harold Lehman, recalled:

“the ideas for early works were] the public use of art, big banners, floats, and big demonstration pieces and things of that nature for parades, gatherings, conventions, meetings. Not particularly for exhibit” J. Mann, The Revolutionary New York Workshop Where Pollock Made Anti-Fascist Art, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-pollock-siqueiros-fought-fascism-radical-art [access on 23.12.2018]↩︎.

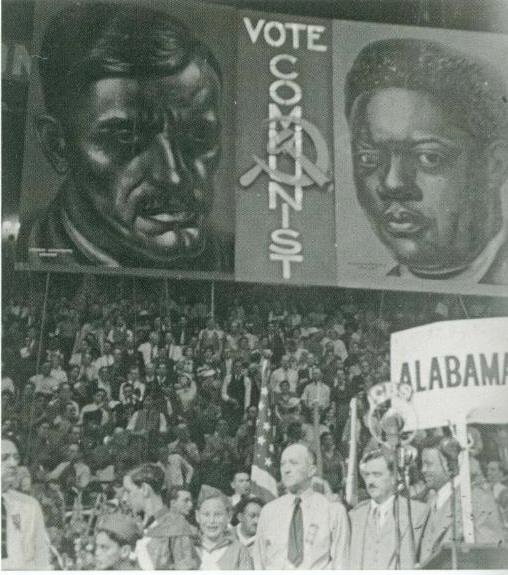

The works created for the purposes of demonstrations and parades, posters, leaflets and scenery of conventions or gatherings are the most complete realization of the idea of Functional Revolutionary Art, on which Siqueiros based the New York Manifesto. For example, the Laboratory produced large-format portraits of its leaders Earl Bowder and James Ford, who were part of the setting of the 9th National Convention of the Party, for the American Communist Party’s conspiracy.

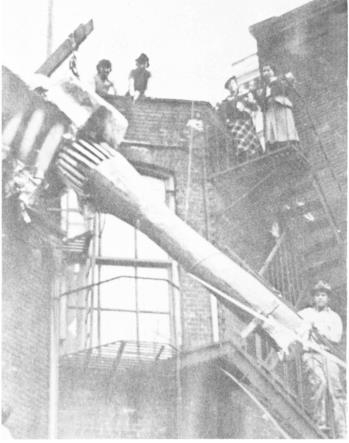

The most interesting form, however, was taken by “functionally revolutionary” sculptures built collectively by the artists in the workshop. Siqueiros himself claimed that modern sculpture should not be a static, vertical monument created using traditional techniques and materials, intended to occupy a privileged place in the city space, museum or collection, but an interactive, multicoloured object with a clear political and social message, which moved in public space, reaching out to the broad masses of the audience and stimulating their revolutionary and emancipatory imagination.

The realization of these assumptions were platforms built to the order of left-wing associations and groupings, used during demonstrations and political demonstrations. The first such object was produced by the Laboratory for the First May parade. It was a mobile, interactive, kinetic sculpture with a distinctly humorous and satirical fervor, which directly criticized American politics and its connections with the world of finance and fascism. It contained a large figure depicting a Wall Street capitalist holding an elephant and a donkey – symbols of the Republican and Democratic Party, indicating that the control over the U.S. policy is held by wealthy financiers, often sympathizing with fascism. At the back of the platform there was a huge hammer, moved by a pendulum, on which the artists painted a sign of the sickle and hammer. As it fell down, the hammer hit the index printer used by stock exchanges in the place of the capitalist’s head, which each time exploded with a fountain of red blood-red tape, which was to symbolize the potential victory of the united U.S. people over the forces of capitalist fascism.

The laboratory also made at least four more platforms, commissioned by the American League Against War and Fascism, which were used during anti-fascist events organized in New York. The first one was prepared for a demonstration against William Hearst, an American press magnate, who favoured the Nazi regime and Hitler. It depicted the sitting figures of Hitler and Hearst, leaning against each other. Their heads were rotating around one axis, swapping places. In creating this double portrait, the artists pointed to the identity of the views of both figures. Lehman also recalled the third float from the workshop, in which:

“a group of worker-soldiers representing the countries allied against the Nazis stood before a papier-mâché Hitler. Between them, mounted on a spring, was a boxing glove attached to a moveable shaft that allowed the soldiers to “punch” the German dictator. “So knock out Hitler!” Ibidem.↩︎.

As the members of the Laboratory recalled, the activity of the undertaking was periodic – moments of intensified work were separated by weeks, during which the workshop was actually dying out completely. A significant proportion of the artists could devote only a small part of their time to the Laboratory – almost all of them had to work for a living to maintain both themselves and the workshop, which was financed by membership fees. At the end of 1936 Siqueiros closed the Laboratory and in early 1937 he joined the International Brigades to fight against fascists in the Spanish Civil War.