American Artists’ Congress

The AAC emerged in the aftermath of changes in the global communist movements which began after the 7th Congress of the Communist International in 1935 at which the overcoming of political divisions and bringing together of all progressive factions was postulated, in addition to the foundation of a global peoples’ front against fascism.

At the beginning, the AAC was treated as an artistic appendage to the communist party but the Congress soon gained autonomy and began an independent association of artists with its own program and ideas for its execution. Officially the Congress commenced its activity in the February of 1936 uniting under a common banner artists who since 1920s had been active members of a range of left-wing artistic trade unions and associations, such as the John Reed Club, the Artists’ Union and the Harlem Artists’ Guild.

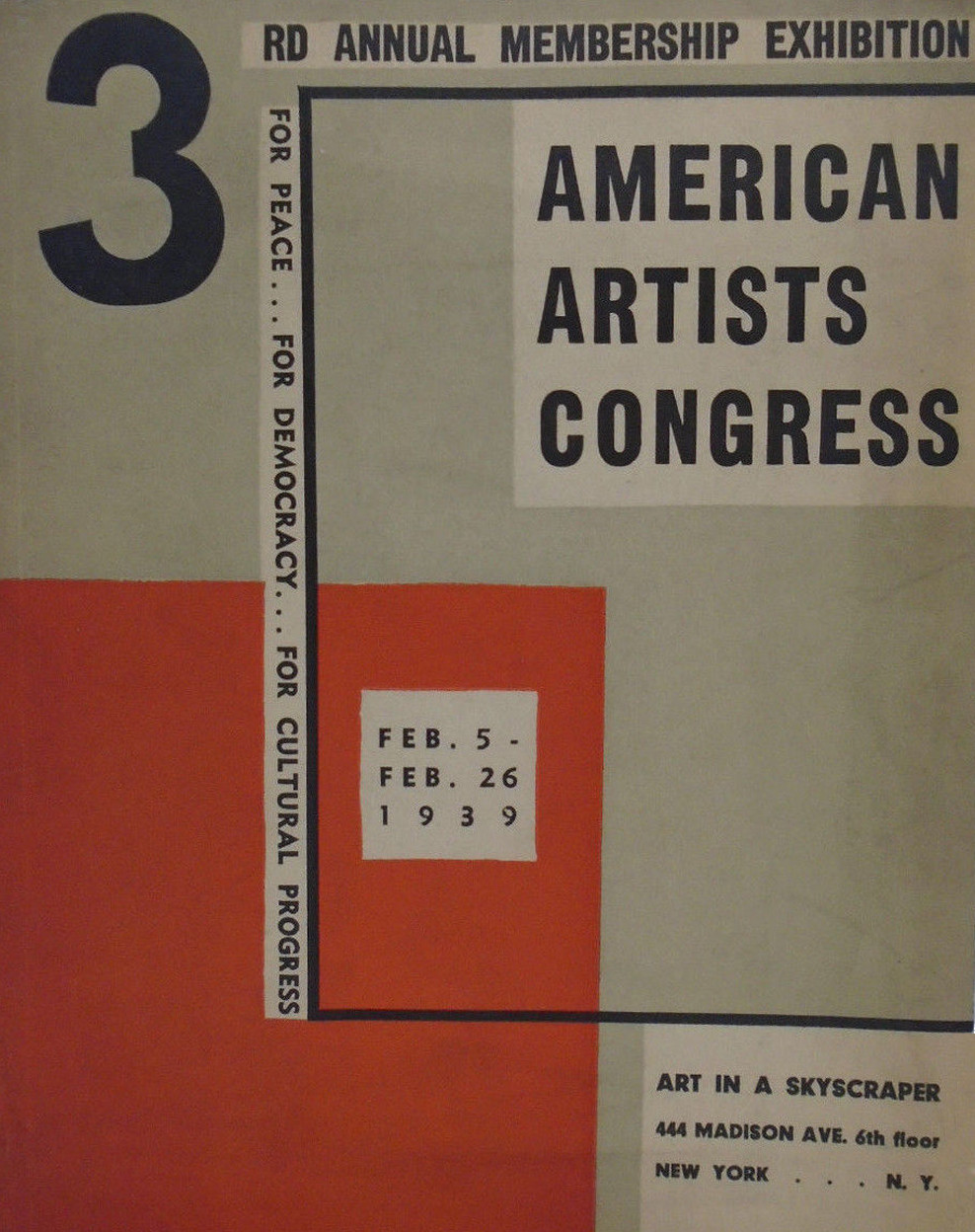

Unlike the John Reed Club, the AAC was a strictly pro-democracy and anti-fascist organization, but not revolutionary or communist in spirit. No political declarations or party loyalty was required from the members and the Congress openly separated itself from the more radical political forces. The AAC’s goal was to unite the artists who protested against the fascist ideology and were willing to engage in collective efforts against fascism through artistic and cultural campaigns and activism. Initially, the organization’s slogan was “Against War and Fascism” but later AAC toned down its platform and changed the slogan to “For Peace, for Democracy, for Cultural Progress. The membership brochure encourage artists to join the AAC read:

“Membership in the Congress is open to any artist of the first rank living in the U.S. without regard to the way he paints or the subject matter he chooses to deal with in his work. The only standard for membership is whether he has achieved a position of distinction in his profession and the only requirement that he support the program of the Congress against war and fascism” . C. Whiting, Antifascism in American Art, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1989.↩︎.

From the very beginning, the AAC attracted many artists and at the end of 1936 had more than 600 members, including Lucile Blanch, Peter Blume, Margaret Bourke-White, Stuart Davis, Mabel Dwight, Hugo Gellert, William Gropper, Minna Harkavy, Louis Lozowick, Anton Refregier, Ben Shahn, David Smith, the Moses Brothers, Raphael Soyer and Meyer Shapiro. Already at the first founding convention in 1936 the organization members officially condemned the fascist ideology. At the next annual meeting in 1937, they strongly objected to Japan’s attack on China and the anti-republican uprising in Spain and declared the need to raise funds to support anti-fascist forces engaged in both conflicts.

Protests and fundraising

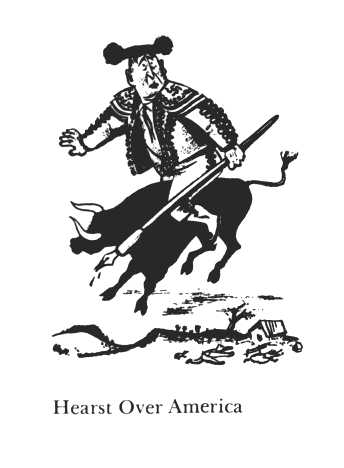

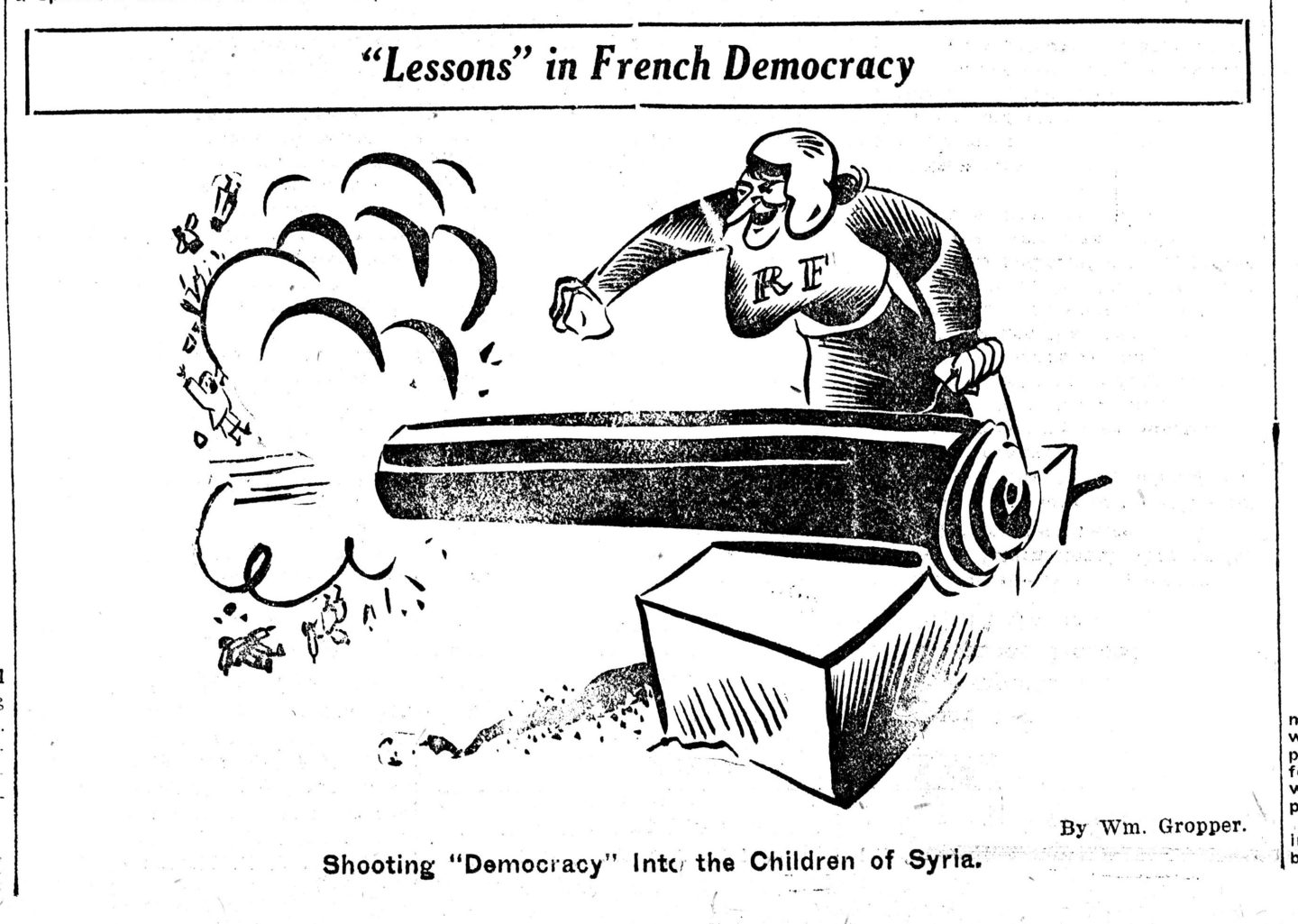

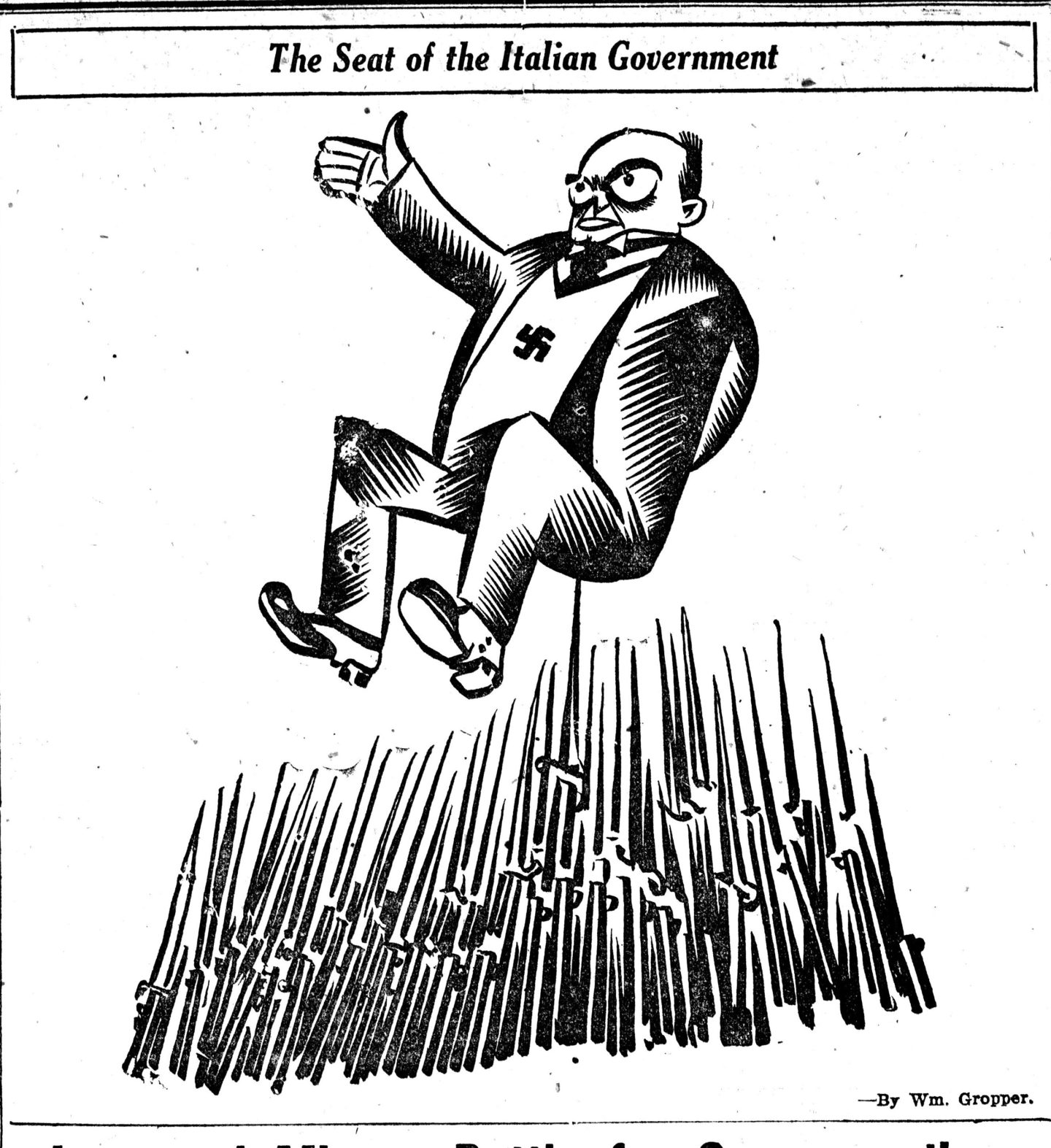

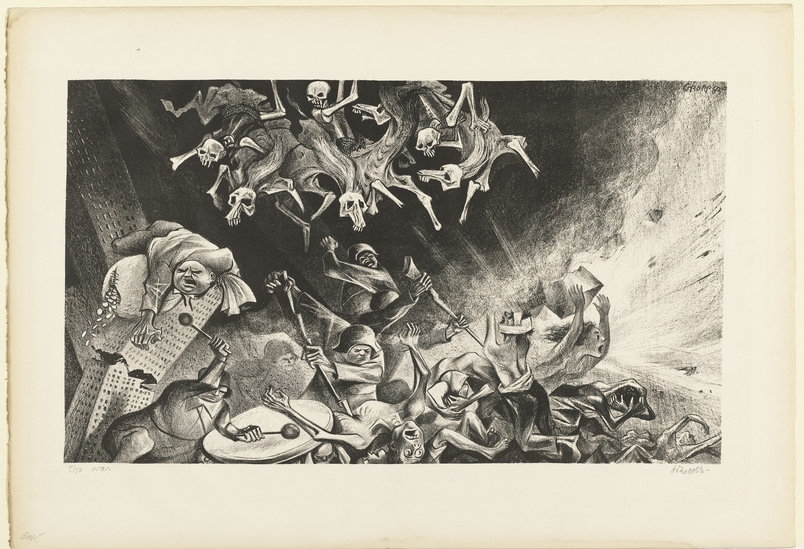

The artists from the AAC were active in many different fields. They fought against censorship, lobbied for a higher public support to artists and tried to promote contemporary American art. The ambition of the Congress members was to reach the widest possible audience with their message. Therefore, they did not only create engaged anti-fascist artworks but also published caricatures and cartoons in popular newspapers and magazines, like the ”Daily Worker” or ”New Masses”. William Gropper known for his satirical acumen was particularly successful in this field.

The AAC members were also among the pioneers of the artistic protest. In order not to legitimize the fascist regime with their art, they refused in 1936 to submit their works for the exhibition organized on the occasion of the Olympics in Berlin and in 1937 did not agree to take part in the Venice Biennale. They also organized one of the first actions to demonstrate their criticism of art institutions. In December 1938, the Congress engaged in a dispute with the Museum of Modern Art in New York (which later got criticized many times by artists and conceptualists associated with the movement of institutional criticism). The organization publicly accused MOMA of providing financial support to the Nazi industry in Germany. According to the artists from the AAC, the famous museum collaborated with the criminal regime as the postcards sold by MOMA with reproduction of the art pieces from its collection were printed in Germany. The management of the institution naturally rejected the accusations, nevertheless, the discussion gained a lot of publicity in the media.

In keeping with the declaration announced at the convention in 1937, the Congress engaged itself in the civil war in Spain trying to mobilize support for the anti-fascist forces fighting in the Iberian Peninsula. In 1938, the AAC organized a live painting session in New York’s Times Square. The organization members, including Philip Evergood, William Gropper, were working on their paintings in front of the passers-by while collecting money for the Spanish republicans. In 1939, the Congress co-organized the showing of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica in the Valentine Gallery in New York. The proceeds of the event were spent on helping the refugees from Spain.

Exhibitions

The most important form of the AAC’s activity was organizing exhibitions. During its term, the Congress launched 22 events, including thematic exhibitions, annual presentations of the Congress members’ works and large shows of drawings and prints. The events were held not only in galleries and universities but also other, frequently popular and prestigious commercial venues (for instance, in 1937 an exhibition was shown in the Rockefeller Center). When searching for appropriate exhibition venues, the AAC could count on the support of the city authorities, including the then Mayor of New York Fiorello La Guardia who considered the Congress as a vital initiative from the cultural and political point of view and agreed to speak at the organization’s second convention in 1937.

The artists from the AAC did not care for prestigious exhibition venues frequented by art experts. Instead, they wanted to reach as many people as possible with their message. The main goal of the organization was to promote anti-war and anti-fascist attitudes through art. The Congress exhibitions were most often travelling shows or were organized in a number of US cities simultaneously.

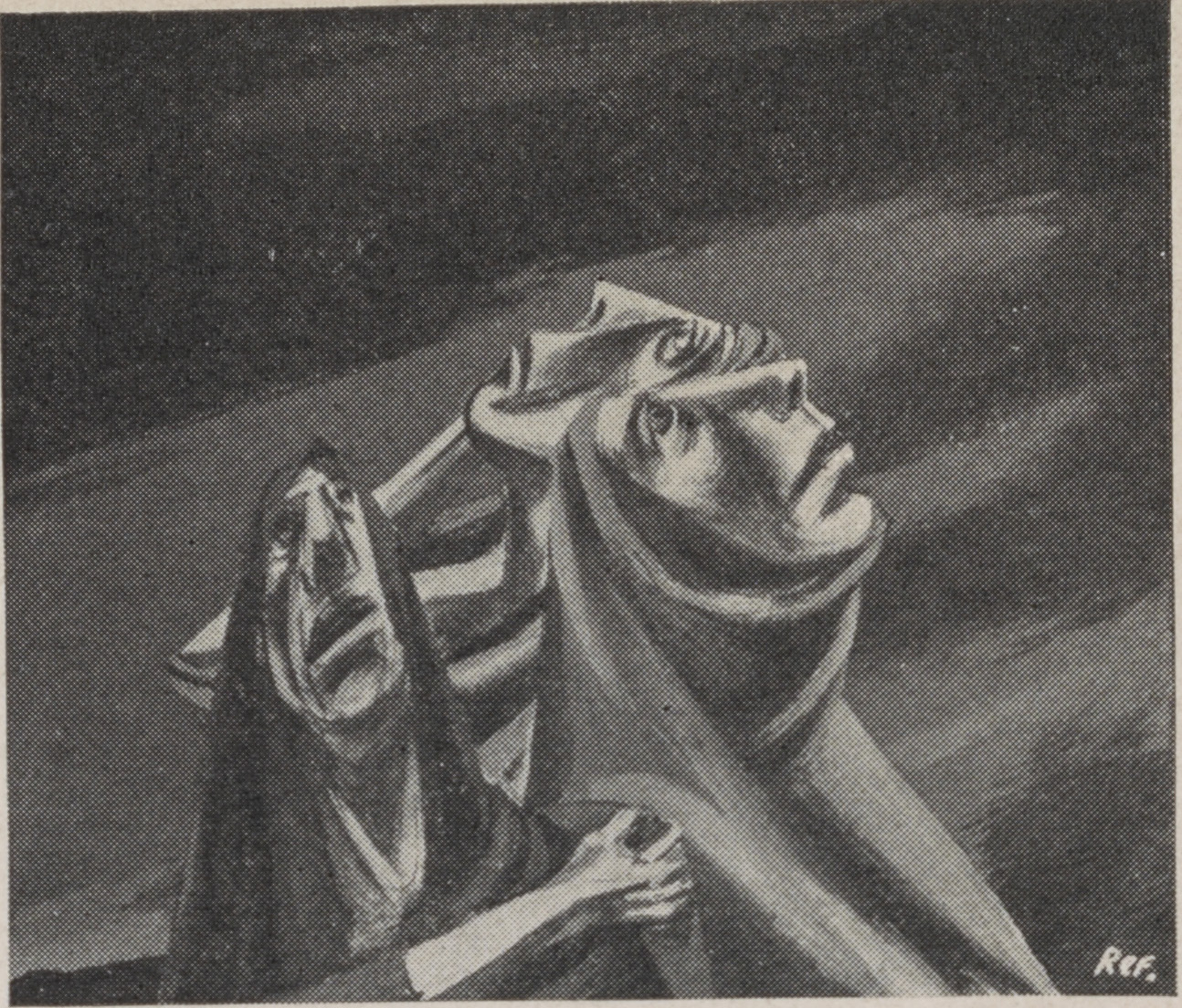

A great majority of works displayed at the annual exhibitions of the ACC’s members were anti-fascist and pacifist paintings, often referring to the subject of the Civil War in Spain. The members openly drew inspiration from the art of Pablo Picasso (especially Guernica) who maintained close contacts with the Congress. The Spanish artist was even supposed to give a speech via the telephone at the Congress meeting in December 1937 but unfortunately a sudden illness thwarted the plan. In the end, Picasso’s speech was read out during the meeting just like an anti-fascist statement by Thomas Mann delivered by the writer’s granddaughter Erika Mann.

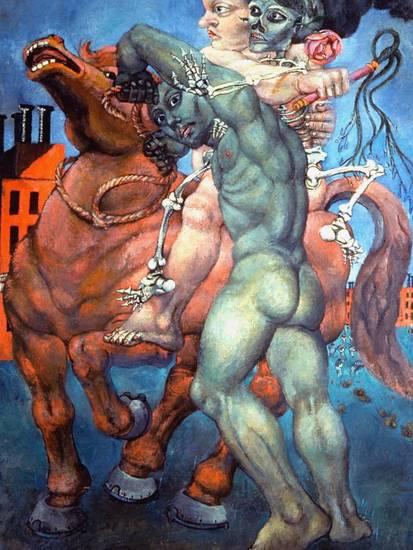

War and Fascism: An International Exhibition of Cartoons Drawings, and Prints

In 1936, the Congress prepared its first exhibition known as the War and Fascism: An International Exhibition of Cartoons Drawings, and Prints in the New School for Social Research in New York on the turn of April and May 1936. The background for the comprehensive review of historical and modern anti-war and anti-fascist works were the frescos by Jose Clemente Orozco of 1931 found on the school walls. The exhibited works included classical pieces by Jacque Callot and Francisco Goya, classical depictions of conflicts, war and destruction by Pieter Breugel, Albrecht Dürer and Honor Daumier, works of active and engaged anti-fascists, German expressionists such as Otto Dix, George Grosz and Käthe Kollwitz and works of Mexican muralists, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. The art community from the United States engaged in anti-war activism was represented by Phil Bard, Mabel Dwight, Hugo Gellert, William Gropper, Reginald Marsh and Mitchell Siporin. Some of the artworks presented at the exhibition were also recorded on a 35 mm on the 35 mm film and offered together with a proposed lecture script to American universities in order to encourage them to teach about the engaged, anti-fascist and anti-war art.

Exhibition in Defense of World Democracy: Dedicated to the Peoples of Spain and China

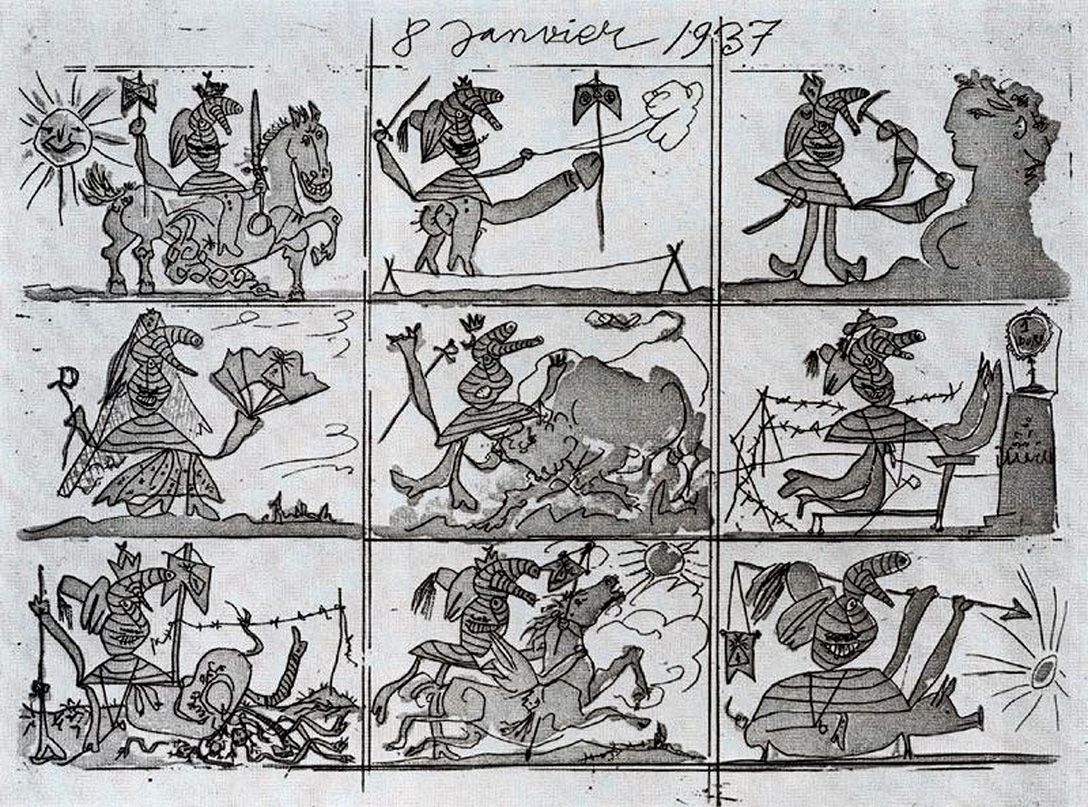

In December 1937, AAC organized the Exhibition in Defense of World Democracy: Dedicated to the Peoples of Spain and China opened at the same time in seven different cities. The exhibition consisted of anti-fascist and anti-war works by such artists as Philip Evergood, William Gropper, Anton Refregier, Minna Harkavy, Lynd Ward, Irene Rice Pereira, Moses Soyer and Yasuo Kuniyoshi. Other displayed works included Philip Guston’s Bombardment being the American artist’s reaction to press articles describing the violence and atrocities during the Civil War in Spain and the famous series of Pablo Picasso’s anti-Franco etchings called the Dream and Lie of Franco some of which prefigured the famous Guernica. The artist planned to sell copies of the panels as postcards to raise funds for the Spanish Republican Government. The idea did not work at the time but was later revived by the members of AAC who during the exhibition sold postcards with the reproductions of Gropper’s, Kuniyoshi’s and Ward’s drawings. All the proceeds from the sale were spent on support for the Spanish anti-fascists.

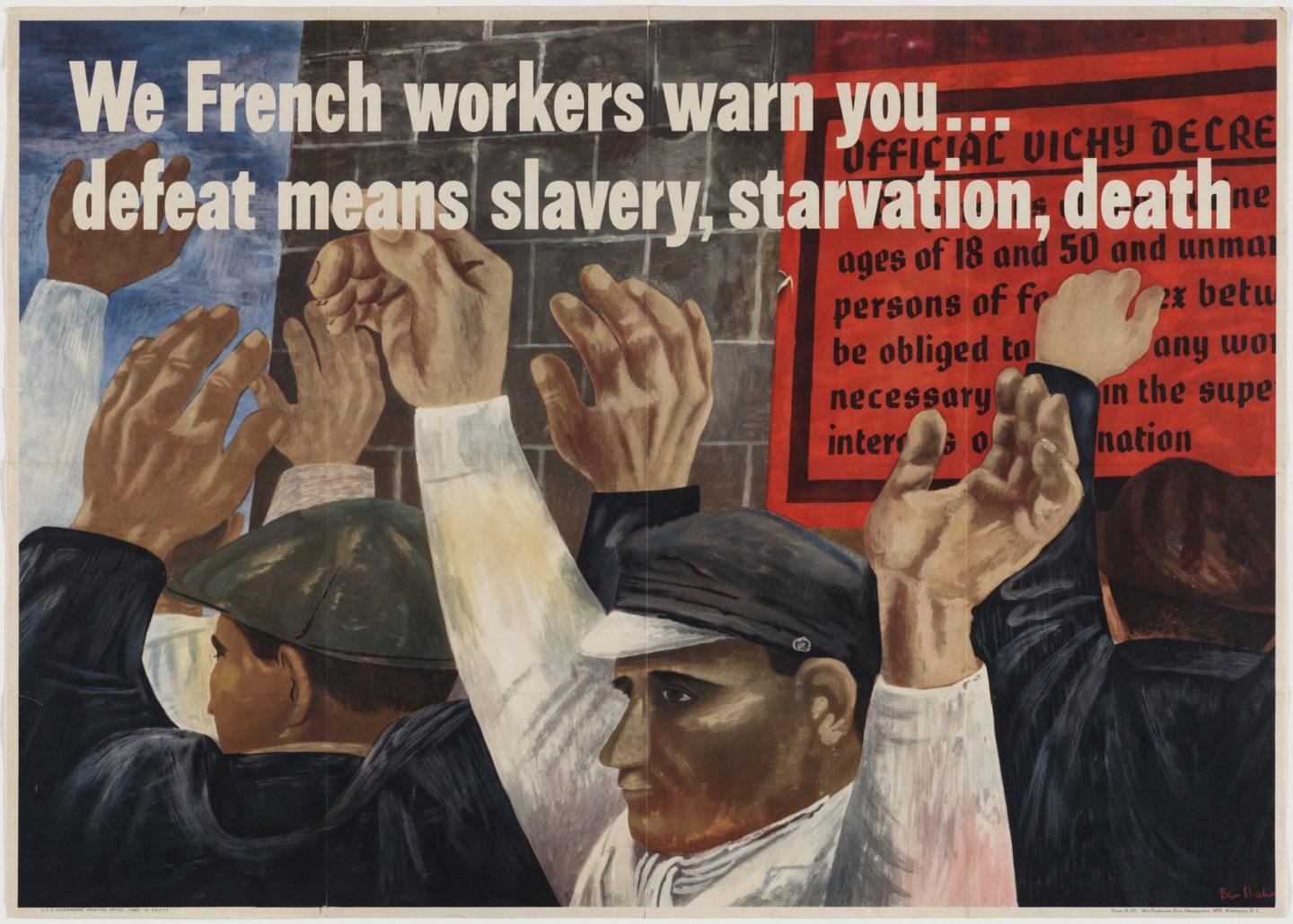

Activities during the Second World War and dissolution of the AAC

In 1939, following the outbreak of WW2 the AAC lost its momentum. In 1940, the Congress refused to condemn the Soviet Union’s invasion on Finland causing a split in the heart of the organization. Many prominent members, including Meyer Shapiro, Lewis Mumford, Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb and Stuart Davis decided to leave the organization. Although formally the ACC continued to exist until 1942, over the last two years its activity was close to none. When the United States got engaged in the Second World War many artists from the Congress began to work for the US government creating anti-fascist and anti-Nazi propaganda materials. Ben Shahn famous for the posters and leaflets designed during the war was particularly successful in that field. The majority of artists who were once members of the Congress continued to created politically engaged, anti-fascist and pacifistic art until the end of their lives.